Friday, June 30, 2006

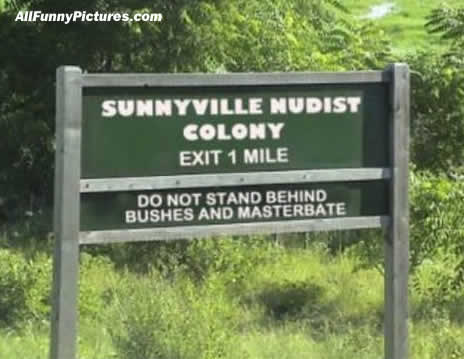

No beating about the bush

After my last few wordy posts, here's one that speaks for itself. Don't blame me for the spelling mistake.

Update!

I've just realised this is the first entry posted on any of the ten million or so existing blogs in the last few years that refers to 'bush' without an ironic tie-in to the US President. Apart from this, of course. Another reason why I'm so great.

Friday, June 23, 2006

Holistic therapy

May I introduce Peter Halvorson, the senior director of ITAG. No, that’s not a new Apple product, but the International Trepanation Advocacy Group. For those who don’t know, trepanation – or trepanning, not to be confused with the charming Cornish town of the same name - is the drilling of a hole in one’s head in order to increase one’s sense of well-being. It was pioneered by one Bart Huges, a Dutch user of mind-bending drugs who gave himself the title ‘doctor’ despite having failed his final exams at medical school and therefore never graduating (as he reveals in this hilarious interview). In his seminal 1962 work on trepanning, The Mechanism of Brain Blood Volume, Huges proposed his concept of Homo sapiens correctus, according to which adults lose the imaginativeness and joie de vivre they experience as small children because the fontanelle, the soft spot on an infant’s head where the bones haven’t fused, closes off and thereby restricts the pulsation of blood in the head. This leads to all manner of problems including depression, neurosis and for all I know the wearing of fake Burberry caps and hoodies. The solution is, obviously, to open a new hole in the skull to allow the blood to pulse and flow more freely, leading to relaxation, relief from mental illness and enhanced creativity. According to this thought-provoking theory, Homo sapiens correctus represents a higher stage in our evolutionary development.

Leaving aside the minor flaws in the hypothesis – one being that if holes in our head were associated with a more natural human state, then natural selection would have provided us with them as adults, perhaps with a hinged flap to keep out infection – there are obvious practical hurdles to overcome in achieving the blissed-out state of cranium violatum. Like, for example, making the hole in the first place. I’ve watched neurosurgery being performed myself and it requires a fair amount of anatomical knowledge, not to mention a steady hand, to penetrate the skull without damaging the brain or its covering layers of dura. Unless you really want the blood to flow spectacularly – torrentially, in fact – it’s probably not such a good idea to rely on a Black & Decker cordless, an eight-pack of Stella and your mate Dougie. You could always try to get a neurosurgeon to do it, I suppose, but for some absurd PC reason doctors in most countries are forbidden by their professional bodies and by law to carry out this procedure, and going to a black market surgeon is risky because there’s usually a very good reason why that doctor is working on the black market in the first place. Fortunately, the ITAG website offers useful tips on how to go about having your skull broken into in a controlled way, and there are some terrific testimonials there, accompanied by pictures of some rather odd-looking people.

I do worry sometimes that I might trepan myself one day. I watched the video nasty Driller Killer once, and I drove a screw through my Action Man’s head when I was a boy. Mind you, I also dismembered him (accidentally) by heaving a pile of rocks onto him to simulate an avalanche, and I haven’t buried myself alive yet, so perhaps I’m reading too much into early behaviour patterns.

Just in case you’re thinking of making the following ‘joke’ in the comments, I’ll save you the bother: I need a hole in my head like I need a hole in the head.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Chameleon (part two)

Following a snide comment by the intolerable Justin Barker, and a polite one by the much nicer Sam, I've divided this into two parts, so there are now two posts for you to skip rather than one.

The effort had been greater this time and the man felt compressed under the heel of fatigue; he sagged so that his head lolled forward and the chains took the full weight of his torso through his arms. He had felt the presence more keenly this time, behind his eyes, and though he had not seen the other’s face he had perceived the beginning of recognition in the flash-second before the communication had been broken, his concentration fracturing on the anvil of exhaustion. The blood soared in his face and his ears and his fingers pricked and tingled and flopped uselessly, cut off from the rest of him by the manacles, but he remained distant from the sensations, allowing his mind to sink into the healing salve of rest…

It was not to be. The door smashed open and the people reached him almost before their shouts, three of them, perhaps fifty, and his hair was grabbed and his head jerked upwards and it was all he could do to smile, not mockingly this time, not coldly, but with a radiance born of his knowledge that what he had done, he had done, and they could not undo it, no matter how they ranted and clawed.

He closed his eyes to await the first of the blows and when it did not come, kept them closed, assuming they were waiting for him to respond, to plead and grovel. But he sensed a movement away from him, the awareness of their proximity dwindling, and when he lifted his head and allowed his lids to part a fraction he saw that they were on either side and another had entered the room and stood at the door gazing at him. The newcomer was faceless as the rest, though with a bearing and an effect on the demeanour of the others which suggested a figure of authority.

The person watched him for a long time, then raised a hand and drew a forefinger across a pale throat and turned and walked out.

Jerry was late and stumbled into the staff room clutching a rueful smile to his face. He had overslept after lying awake until three, his mind awash not with computers but with psychosis, the disintegration of rationality, labels and drugs and prognoses and the awful shame and contempt he would see in Rachel’s pinched face.

The meeting had started already and Whittaker, the head master, flashed his spectacles.

‘I was just saying that the substitute for Shirley has cancelled at short notice.’

Friday, he promised himself. I’ll give it till Friday, then I’ll go and see the doctor.

‘So I’d like you to take her classes for the time being, Jerry.’

He felt as though something hard had lodged in his gullet. Taking on the extra load would mean doubling his evening marking, cancelling the half-day course he’d booked for Wednesday…

‘There’s no problem with that, I hope?’

He beamed. ‘No, that’s great. Be a bit of a challenge.’ Bryant could do it, he’d taught history before, he sat around on his backside all day – no, give him a break, he had some personal problems.

The meeting crawled on, Whittaker’s voice like the static on the fringes of a radio channel’s sound, and Jerry nodded and made the required noises and tugged a fingertip around the rim of his collar and wondered why he breathed as though through a grime-clogged gag, until movement at the far reach of his vision turned his head and in the mirror on the wall he saw his face, empurpled and bulging, and the end of his tie held aloft by an unseen force while the loop at the other end shrank tightening into his neck.

The suddenness of the connection made the man recoil, more even than the image he received, and the back of his head cracked against the wall. He sat staring at the ceiling, his heart clapping so that he was sure it would slip the smooth mechanism of its regular rhythm and jerk unco-ordinated and ineffectual in his breast.

It had been a single strobe-flicker in his head, the instant of communication, and he knew the bond was stronger and closer now because the other, the one with whom he had made contact, had anticipated, and unwittingly sent this awareness to him. His frustration was great, more intense than his fear, because the other was unaware of what he knew and the power he had, and would carry the seed of this knowledge and power in him, unfertilized by attention and unnurtured by the rain of purpose, while the man he could have saved slipped away into the blankness of non-being.

His gaze snapped to the door as it opened and the people came in, more of them this time than he could remember before, and he prepared his muscles and his jaws for a final onslaught, but their numbers were too great this time and they pinned him easily as they unlocked the fetters in silence and hauled him to his feet, their arms contributing the strength his puny legs lacked, and half-dragged him towards the open door.

Cold rain slick on his face as he leaned on the railing of the balcony and heaved in lungfuls of air. His top button was undone and his tie loosened but the pressure on his throat had not gone, though outwardly he seemed to reveal nothing, as nobody had remarked on his appearance in the staff room.

Doreen, one of the maths teachers, appeared at his side. ‘All right?’

‘Yes, fine.’ He glanced swiftly at her but it had been a general greeting, not a question. She was fifty, with a worn yet soft face, and eyes that made him uncomfortable because they seemed never merely to look at him but to see him.

‘Jerry, it’s not my place, but Whittaker really put one over on you in there.’

Go away. ‘Oh, I don’t know.’

She turned towards him and he twisted inwardly. ‘I’m serious. Covering for Shirley is Bryant’s job, and they both know it.’

He lifted a palm skyward in a shrug and hoped his sigh conveyed exasperated cheer. ‘It’s no big deal, Doreen. Besides, I’m at my best when I’m stretched.’

She watched him a moment and then dipped her eyelids and smiled. ‘Okay. Whatever.’ She started away down the corridor and he looked at her dwindling shape and for an instant so brief it was like a thought-fragment, she was not a short dumpy woman but a slight, bowed man in white, carried on either side by featureless figures towards a distant dreadful silhouette, and something stifled within him twitched violently.

Then the shocking howling of the bell on the wall behind him shook him upright and he pushed away from the rail and set off towards his classroom.

He did not open his mouth, for fear that his tongue would mock him by spewing a gabble of apologies and pleas; he did not close his eyes, in case the primal darkness drove him to seek escape by the same route. On the way, a hundred paces beyond the door, they had paused, and he had surged as they had wavered, but the journey had resumed and he had felt sick at how the imagination which had protected him throughout the years and decades in the room, was now ridiculing him with the sneer of false hope.

The man stood on the platform while the manacles were locked around his wrists behind his back. Before him, thrown by light from behind him, his thin shadow formed a grotesque hybrid with that of the scaffold above his head, man and the means of his death fused in an ironic whole.

The ground he had traversed was grey ash and the wall in which the door was set, the door through which he had passed, was of a dullness that made the inside of the room seem bright as dawn by comparison. He knew that the outside, the world beyond the door, had changed since he had been a child, that this uniform paleness was all that remained after its vividness and life had been leached away. He did not know where the colour had gone.

There was movement behind him and he started, but his attention had been caught by the impossible stirring of the wall beside the door, as though part of it were detaching itself. He saw the figure of a man standing against the wall, slightly hunched, the features unclear because of the similarity in colour between figure and background. Instantly, he realised he knew the man.

The contact was immediate this time, with little effort required on his part, and all at once he was inside the head of the man against the wall, and the sensation was unnerving. He was looking through the familiar stranger’s eyes, and his vision was not stereoscopic but seemed to cover two constantly-changing fields simultaneously, all incoming information being rapidly evaluated and, if it did not appear to signify threat, disregarded. His face felt compressed as if against imminent attack; his hands clutched themselves; his urge to move his limbs forced up against an equal compulsion to be still.

For a moment, the contact flickered, and the roughness of the people’s hands was upon him and the agitation of their voices was driven less by anger than by fear. He smiled, and drew the thin air in through his mouth until he could expand himself no further, and called out from the depths of his self.

The eyes of the other swivelled so that for the first time they focused in the same place, and through them he saw himself, the hurried fitting of the noose and the hand impatient on the lever.

Even with his eyes closed, he could see the sun burning a hole through the bleak swollen clouds. He raised his face to it, wanting to climb on the railing and reach for it, let it scorch his hands and his body, consume him.

He stared down the corridor. Doreen was at the end, unlocking a door. He called out and when she looked up, he ran towards her, laughing at her alarm.

‘Jerry, what - ?’

He stood before her, breathing heavily, tears stinging his eyes, not caring. ‘You’re right. Thanks.’

He turned, for the first time in his adult life not waiting for a response.

Whitaker was talking to a parent outside his office and held up a hand to warn Jerry to wait. When the woman had gone he raised a bland eyebrow. ‘Something?’

‘Two things, in fact.’ The enormity of what he was about to do was making him wheeze. He went ahead and wheezed. ‘Firstly, I’d rather you didn’t dismiss me as you just did, as though I’m one of the kids.’

Whitaker flinched as though bitten. He opened his mouth.

‘Secondly, I haven’t the time to cover for Shirley. I’m willing to help out in a pinch, as I’ve demonstrated more than once, but it’s time other people started pulling their weight.’ He paused. ‘That’s all.’

Terror clawed up at his throat from deep inside his belly, real terror, not the small dreary empty thing that had been clinging to him like a whining child for as long as he could remember. The pain of it was intense and pure, and good.

He was late for class, and two boys in the front row glanced round at him as he entered and then turned back to the telling of a story, each sentence punctuated by an obscenity. He approached, sweating, and stood over them until the silence of the others made them look up at him again.

‘I won’t have that sort of language in my classroom.’

One of the boys was cowed; the other held his hands up in pantomime horror. Jerry stood back and pointed at the door with his thumb.

‘Get out.’

A torrent of invective, but the boy left eventually with a final remark that his dad would sort Jerry out. Jerry smiled and sat down. Let him. Just let him come.

When the class had gone, the last of the girls peering at him in uneasy wonder as she passed his desk, he sat alone as he had never been before, and waited to be swamped with shock. He thought of Rachel, and the puzzled fearful look she would give him as he walked to her from his car that evening; of the conversation they would have, and the terrible exhilarating unknowability of the course their lives would take after it, together or separately; of the uncertainty and strangeness of a world in his hands and not under the stewardship of others.

He did feel shock, that which accompanies the experience of everything new that is of any value; he did feel regret for the dust of long-dead opportunities that whispered in the murmurings of memory that were now audible to him, no longer obscured by the chattering of impossible dilemmas and ridiculous, petty preoccupations. But what he felt most deeply was hunger, a hunger that was like a furnace the door of which had suddenly been flung open, with flames that needed constant stoking to prevent them from leaping out and consuming him and in return provided him with fuel without limit.

He picked up his diary and paged through it until the letters caught his eye and he looked at them for a long time, noticing two things: the handwriting was his own, and the words were no longer Help me but Thank you.

The man stood alone, the last of his captors having faded silently. To his left was the scaffold, a pathetic skeleton of corrupt wood and rope; to his right, the wall with its door, which stood ajar. Before him the ground stretched, still ash-grey but with a raw expectant character that suggested it was not dead, merely fallow. There was no path to speak of, or alternatively, there was an infinite number of paths.

The manacles were gone from his wrists and he found them behind the platform, rusted and cold. He slipped them into a pocket and when he straightened up, he saw that the door in the wall had opened further, and warm light spilled from the room beyond. Warm, colourless light.

He watched as the doorway was fully exposed and the impossibly large room was revealed, and even from where he stood he could identify childhood playthings scattered on its floor as the music of his own young laughter called to him. The toys were red and yellow and blue, but their brightness was desperate, as though it would slip free and dissipate at any moment.

He raised his head, and smiled, and turned his back on the door and began to walk away towards the horizon.

The effort had been greater this time and the man felt compressed under the heel of fatigue; he sagged so that his head lolled forward and the chains took the full weight of his torso through his arms. He had felt the presence more keenly this time, behind his eyes, and though he had not seen the other’s face he had perceived the beginning of recognition in the flash-second before the communication had been broken, his concentration fracturing on the anvil of exhaustion. The blood soared in his face and his ears and his fingers pricked and tingled and flopped uselessly, cut off from the rest of him by the manacles, but he remained distant from the sensations, allowing his mind to sink into the healing salve of rest…

It was not to be. The door smashed open and the people reached him almost before their shouts, three of them, perhaps fifty, and his hair was grabbed and his head jerked upwards and it was all he could do to smile, not mockingly this time, not coldly, but with a radiance born of his knowledge that what he had done, he had done, and they could not undo it, no matter how they ranted and clawed.

He closed his eyes to await the first of the blows and when it did not come, kept them closed, assuming they were waiting for him to respond, to plead and grovel. But he sensed a movement away from him, the awareness of their proximity dwindling, and when he lifted his head and allowed his lids to part a fraction he saw that they were on either side and another had entered the room and stood at the door gazing at him. The newcomer was faceless as the rest, though with a bearing and an effect on the demeanour of the others which suggested a figure of authority.

The person watched him for a long time, then raised a hand and drew a forefinger across a pale throat and turned and walked out.

Jerry was late and stumbled into the staff room clutching a rueful smile to his face. He had overslept after lying awake until three, his mind awash not with computers but with psychosis, the disintegration of rationality, labels and drugs and prognoses and the awful shame and contempt he would see in Rachel’s pinched face.

The meeting had started already and Whittaker, the head master, flashed his spectacles.

‘I was just saying that the substitute for Shirley has cancelled at short notice.’

Friday, he promised himself. I’ll give it till Friday, then I’ll go and see the doctor.

‘So I’d like you to take her classes for the time being, Jerry.’

He felt as though something hard had lodged in his gullet. Taking on the extra load would mean doubling his evening marking, cancelling the half-day course he’d booked for Wednesday…

‘There’s no problem with that, I hope?’

He beamed. ‘No, that’s great. Be a bit of a challenge.’ Bryant could do it, he’d taught history before, he sat around on his backside all day – no, give him a break, he had some personal problems.

The meeting crawled on, Whittaker’s voice like the static on the fringes of a radio channel’s sound, and Jerry nodded and made the required noises and tugged a fingertip around the rim of his collar and wondered why he breathed as though through a grime-clogged gag, until movement at the far reach of his vision turned his head and in the mirror on the wall he saw his face, empurpled and bulging, and the end of his tie held aloft by an unseen force while the loop at the other end shrank tightening into his neck.

The suddenness of the connection made the man recoil, more even than the image he received, and the back of his head cracked against the wall. He sat staring at the ceiling, his heart clapping so that he was sure it would slip the smooth mechanism of its regular rhythm and jerk unco-ordinated and ineffectual in his breast.

It had been a single strobe-flicker in his head, the instant of communication, and he knew the bond was stronger and closer now because the other, the one with whom he had made contact, had anticipated, and unwittingly sent this awareness to him. His frustration was great, more intense than his fear, because the other was unaware of what he knew and the power he had, and would carry the seed of this knowledge and power in him, unfertilized by attention and unnurtured by the rain of purpose, while the man he could have saved slipped away into the blankness of non-being.

His gaze snapped to the door as it opened and the people came in, more of them this time than he could remember before, and he prepared his muscles and his jaws for a final onslaught, but their numbers were too great this time and they pinned him easily as they unlocked the fetters in silence and hauled him to his feet, their arms contributing the strength his puny legs lacked, and half-dragged him towards the open door.

Cold rain slick on his face as he leaned on the railing of the balcony and heaved in lungfuls of air. His top button was undone and his tie loosened but the pressure on his throat had not gone, though outwardly he seemed to reveal nothing, as nobody had remarked on his appearance in the staff room.

Doreen, one of the maths teachers, appeared at his side. ‘All right?’

‘Yes, fine.’ He glanced swiftly at her but it had been a general greeting, not a question. She was fifty, with a worn yet soft face, and eyes that made him uncomfortable because they seemed never merely to look at him but to see him.

‘Jerry, it’s not my place, but Whittaker really put one over on you in there.’

Go away. ‘Oh, I don’t know.’

She turned towards him and he twisted inwardly. ‘I’m serious. Covering for Shirley is Bryant’s job, and they both know it.’

He lifted a palm skyward in a shrug and hoped his sigh conveyed exasperated cheer. ‘It’s no big deal, Doreen. Besides, I’m at my best when I’m stretched.’

She watched him a moment and then dipped her eyelids and smiled. ‘Okay. Whatever.’ She started away down the corridor and he looked at her dwindling shape and for an instant so brief it was like a thought-fragment, she was not a short dumpy woman but a slight, bowed man in white, carried on either side by featureless figures towards a distant dreadful silhouette, and something stifled within him twitched violently.

Then the shocking howling of the bell on the wall behind him shook him upright and he pushed away from the rail and set off towards his classroom.

He did not open his mouth, for fear that his tongue would mock him by spewing a gabble of apologies and pleas; he did not close his eyes, in case the primal darkness drove him to seek escape by the same route. On the way, a hundred paces beyond the door, they had paused, and he had surged as they had wavered, but the journey had resumed and he had felt sick at how the imagination which had protected him throughout the years and decades in the room, was now ridiculing him with the sneer of false hope.

The man stood on the platform while the manacles were locked around his wrists behind his back. Before him, thrown by light from behind him, his thin shadow formed a grotesque hybrid with that of the scaffold above his head, man and the means of his death fused in an ironic whole.

The ground he had traversed was grey ash and the wall in which the door was set, the door through which he had passed, was of a dullness that made the inside of the room seem bright as dawn by comparison. He knew that the outside, the world beyond the door, had changed since he had been a child, that this uniform paleness was all that remained after its vividness and life had been leached away. He did not know where the colour had gone.

There was movement behind him and he started, but his attention had been caught by the impossible stirring of the wall beside the door, as though part of it were detaching itself. He saw the figure of a man standing against the wall, slightly hunched, the features unclear because of the similarity in colour between figure and background. Instantly, he realised he knew the man.

The contact was immediate this time, with little effort required on his part, and all at once he was inside the head of the man against the wall, and the sensation was unnerving. He was looking through the familiar stranger’s eyes, and his vision was not stereoscopic but seemed to cover two constantly-changing fields simultaneously, all incoming information being rapidly evaluated and, if it did not appear to signify threat, disregarded. His face felt compressed as if against imminent attack; his hands clutched themselves; his urge to move his limbs forced up against an equal compulsion to be still.

For a moment, the contact flickered, and the roughness of the people’s hands was upon him and the agitation of their voices was driven less by anger than by fear. He smiled, and drew the thin air in through his mouth until he could expand himself no further, and called out from the depths of his self.

The eyes of the other swivelled so that for the first time they focused in the same place, and through them he saw himself, the hurried fitting of the noose and the hand impatient on the lever.

Even with his eyes closed, he could see the sun burning a hole through the bleak swollen clouds. He raised his face to it, wanting to climb on the railing and reach for it, let it scorch his hands and his body, consume him.

He stared down the corridor. Doreen was at the end, unlocking a door. He called out and when she looked up, he ran towards her, laughing at her alarm.

‘Jerry, what - ?’

He stood before her, breathing heavily, tears stinging his eyes, not caring. ‘You’re right. Thanks.’

He turned, for the first time in his adult life not waiting for a response.

Whitaker was talking to a parent outside his office and held up a hand to warn Jerry to wait. When the woman had gone he raised a bland eyebrow. ‘Something?’

‘Two things, in fact.’ The enormity of what he was about to do was making him wheeze. He went ahead and wheezed. ‘Firstly, I’d rather you didn’t dismiss me as you just did, as though I’m one of the kids.’

Whitaker flinched as though bitten. He opened his mouth.

‘Secondly, I haven’t the time to cover for Shirley. I’m willing to help out in a pinch, as I’ve demonstrated more than once, but it’s time other people started pulling their weight.’ He paused. ‘That’s all.’

Terror clawed up at his throat from deep inside his belly, real terror, not the small dreary empty thing that had been clinging to him like a whining child for as long as he could remember. The pain of it was intense and pure, and good.

He was late for class, and two boys in the front row glanced round at him as he entered and then turned back to the telling of a story, each sentence punctuated by an obscenity. He approached, sweating, and stood over them until the silence of the others made them look up at him again.

‘I won’t have that sort of language in my classroom.’

One of the boys was cowed; the other held his hands up in pantomime horror. Jerry stood back and pointed at the door with his thumb.

‘Get out.’

A torrent of invective, but the boy left eventually with a final remark that his dad would sort Jerry out. Jerry smiled and sat down. Let him. Just let him come.

When the class had gone, the last of the girls peering at him in uneasy wonder as she passed his desk, he sat alone as he had never been before, and waited to be swamped with shock. He thought of Rachel, and the puzzled fearful look she would give him as he walked to her from his car that evening; of the conversation they would have, and the terrible exhilarating unknowability of the course their lives would take after it, together or separately; of the uncertainty and strangeness of a world in his hands and not under the stewardship of others.

He did feel shock, that which accompanies the experience of everything new that is of any value; he did feel regret for the dust of long-dead opportunities that whispered in the murmurings of memory that were now audible to him, no longer obscured by the chattering of impossible dilemmas and ridiculous, petty preoccupations. But what he felt most deeply was hunger, a hunger that was like a furnace the door of which had suddenly been flung open, with flames that needed constant stoking to prevent them from leaping out and consuming him and in return provided him with fuel without limit.

He picked up his diary and paged through it until the letters caught his eye and he looked at them for a long time, noticing two things: the handwriting was his own, and the words were no longer Help me but Thank you.

The man stood alone, the last of his captors having faded silently. To his left was the scaffold, a pathetic skeleton of corrupt wood and rope; to his right, the wall with its door, which stood ajar. Before him the ground stretched, still ash-grey but with a raw expectant character that suggested it was not dead, merely fallow. There was no path to speak of, or alternatively, there was an infinite number of paths.

The manacles were gone from his wrists and he found them behind the platform, rusted and cold. He slipped them into a pocket and when he straightened up, he saw that the door in the wall had opened further, and warm light spilled from the room beyond. Warm, colourless light.

He watched as the doorway was fully exposed and the impossibly large room was revealed, and even from where he stood he could identify childhood playthings scattered on its floor as the music of his own young laughter called to him. The toys were red and yellow and blue, but their brightness was desperate, as though it would slip free and dissipate at any moment.

He raised his head, and smiled, and turned his back on the door and began to walk away towards the horizon.

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

Chameleon (part one)

When Rachel opened the door to Jerry he knew at once that something was wrong. The quick, tight smile, gone as if it had never been there, the fine crease between her brows, the way she toyed with the nail of her index finger against the pad of her thumb, were all unmistakeable signs of unease, and he felt dismay rise listlessly in him like an arthritic dog dragging itself to its feet on command.

He locked the door of the Honda and swung his coat over one shoulder and walked to her, his face set in the expression of concern-tinged cheerfulness he had mastered long ago. He received and returned the kiss and followed her into the house, hanging the jacket on its peg and walking after her into the kitchen, where he perched on one of the two wooden stools at the small breakfast table and watched her at the stove.

Yes, not bad, the day.

Yes, the staff meeting had gone okay, a few protests about the forthcoming inspection but nothing major.

No, it had been the fifth-formers for two periods today, the sixth form was Wednesday.

How had her day been?

And on it went, he with his cup of tea, she half-turned towards him at the cooker, the saucepans simmering quietly and an undefinable aroma in the air.

Through the dinner of lasagna and salad, which he liked and told her he liked, he began to breathe more easily, letting the concern fade slowly from his eyes and his mouth; perhaps it wasn’t necessary. Television tonight, then, probably, the drama series they both enjoyed, and half an hour catching up with his e-mail, and then perhaps, at bed-time, a casual word, affectionately and humorously put, to the effect that she had seemed upset when he had come home and he was glad she was all right.

‘Samantha’s pregnant.’

He had been about to say something, the silence shading into discomfort, and he felt relief that she had spoken and then confusion at what she had said, at how he was supposed to react. She wasn’t looking at him and he had time to rummage through his closet of expressions and throw one on: the raised-eyebrow grin.

‘Really? That’s great.’ He gave it two seconds and followed up with, ‘When did she find out?’

‘Yesterday.’

She raised her head and he searched her eyes secretly. He couldn’t process what he saw there quickly enough so he said, boldly, ‘When’s she due?’

‘June, probably.’ She looked down at her plate. It was too much for him and he smiled and said, ‘Hm,’ and went on eating, wanting to flee, to bare his face to the cold dark autumn and run until the pain sawed his chest ragged.

Except that he didn’t. He wanted to be with Rachel, to comfort her, to make it right and to make her happy. Because he loved her.

He stood at the kitchen window, mug in hand, staring at the neat scrap of lawn with its spill of leaves at the border, at the stack of wooden boards and tiles that leant against the shed, raw materials for the kennel that had never been, for the dog that, he agreed with her, they could not afford. They had passed the evening as planned, side by side on the sofa, enjoying the drama on the television, except he had felt he was enjoying it more than she was; afterwards he had sat at his computer and read his mail and sent replies, while the sounds in the other room suggested she was on the telephone and he strained his ears desperately.

He made up his mind, and closed his eyes for a moment, and then went back into the living room where she was on the settee again, legs curled up under her. He sat beside her and smiled softly and said, ‘I’ve been thinking about it. For a while now, actually. Let’s have a baby.’

The room was white, a brilliant newly-washed white that extended into the farthest recesses where wall met ceiling. The man had covered every inch, moving his gaze as slowly as he could, seeking a sign that the purity of the wall and ceiling and floor was sullied, and failing. He had rubbed at the wall against which he sat with his head and the backs of his hands, and craned his head round to peer painfully at the wall out of the corner of his eye, searching for a smudge, an acknowledgement from the cold stone surface that he had marked it, that he existed, but the blankness remained.

The room was a cube, ten feet to a side, with a white door directly opposite him through which people came. He could see no handle on the door but the people who came always seemed to find one to let themselves out. He did not know how he could estimate the size of the room, or how he knew what a door was; no-one had ever taught him such things. He had been in the room as long as he could remember, and that was as far back as his infancy. In his childhood, he had run free in the room, and it had been larger then, much larger; it was not, he knew, merely his changed perspective as an adult that made it appear that the room had shrunk.

The man sat with his back pressed against the hardness of the wall and his knees drawn up before him. His knees were bony, and he knew the people would soon come in and change his colourless clothes for a set of a smaller size, the changing garb keeping pace with the shrivelling of his physique. His arms were stretched above him and away from him in a flattened Y shape, and they remained this way except when the people came to change his clothes, when he shook them and rubbed them and ignored the shouted orders to keep still until the manacles at the ends of the chains bolted into the wall were snapped into place around his wrists once more.

He could not remember when the chains had first been used to hold him. As a boy, he had been vaguely aware of their presence, two unobtrusive and therefore uninteresting features on the wall; but the wall, and the rest of the room, had not been as blank then, and he was unsure whether he imagined that it had been altogether a different colour, perhaps multicoloured, with vivid pictures the details of which eluded him now. It was as though he had been drugged for days, years even, so that his life had washed about him in a dimly-perceived and timeless sea until he had risen to full consciousness and found himself a prisoner, diminished and betrayed.

Yet he had not turned in on himself, displaying his throat for the people to cut. He pulled at the chains until his wrists were scraped raw; he yelled and cursed and spat in the faces of the people when they came in with food or clothing; he wrenched his failing body towards the half-open door whenever it opened, and earned abuse and slaps and blows sometimes. He did not know what lay beyond the door, although he had glimpsed things through it as a child that he had not understood but which had reassured him. As a man, he no longer derived any comfort from the thought of what was outside, and he knew therefore he must discover it.

At the first note of the bell the banks of protocol gave way to a shouting torrent of teenagers and Jerry went through the motions of dismissing the class, his voice louder than usual but unheeded. The last person to leave, a sullen owl-eyed girl called Zoe, passed his desk and he beamed at her; she stared back blankly and he moved a pile of exercise books from one side of his desk to another. The last double-period of the week, and he really felt he was getting somewhere with them, infecting them with his enthusiasm for the Tudors.

He had a free period and found Halford, the vice-principal, in the staff room. Jerry poured coffee and frowned, ‘They’re not as bad as I was told, actually. Form Six.’

Halford bobbed his eyebrows. ‘Then you’ve more patience than I have. I’d have achieved more talking to my reflection for forty minutes yesterday than standing up in front of that lot.’

Jerry laughed. ‘Thing is, I really want to make a difference, it’s why I went into teaching in the first place. If I can get just one of them interested, it’ll be worth it.’

‘Two or three of them need a good whack, that’d get them all interested,’ said Halford through cigarette smoke.

Jerry felt a tweak of annoyance. ‘Yep, can’t argue there,’ he grinned. Halford had been teaching fifteen years, knew what he was talking about.

Halford had his head in a newspaper and Jerry took out his diary for something to do and began paging. Rachel’s parents were coming up for the weekend, which he didn’t mind even though he had been planning to get his new website sorted out. There was always –

He had turned the page by the time he registered the words and he flipped back.

Help me.

The letters were large, in bold black ink, in the centre of the page. He had not written them. He was sure of it.

Rachel? One of his pupils?

Help me.

He riffled through the book but glimpsed nothing similar. He looked up but Halford was hidden behind his paper and seemed to have noticed nothing.

He was frightened.

The beatings were harder this time and the man shrank into himself as far as his manacled, exposed position allowed. There were kicks to his stomach, slaps to his cheeks, cuffs to his head, and he clenched his eyes and his jaws and endured. He endured because for the first time in as long as he could remember, his hope was real, not an abstract, free-floating concept but one rooted in the world. He had seen, in the broadest and most metaphorical sense of the word, another, who could help him, and he had communicated his desire for help in a manner which he did not begin to understand, but which had been effective. He did not know how the people who were beating him knew of this contact, and he did not care. What mattered to him was that he had achieved, that his actions had had an influence, and the knowledge was a spur to his rage and his joy. The blows came faster, and his tormentors screamed spittle at him, and he began to laugh, to himself at first, and then at them, in their faces, and although this drove their fury to heights and depths he had not experienced before, the resulting pain insulated him from fear and despair, the irony of which made him scorn them all the more.

Later, when they had gone in a throng of muttered contempt and revulsion, he slumped bloodied and exhausted against the wall, his eyes swollen almost shut and his mouth numb; but he did not sleep, even though his body screamed at him for the release of unconsciousness. The giddying sensation of his contact with the other was fresh in him, and he extended his awareness outwards instead of towards his core and let himself drift and probe…

‘Rachel tells us you’re into computers.’

Jerry topped up Dorothy’s wineglass. She was his mother-in-law, an austere sixty with arched artificial eyebrows and eyes that gleamed bitterness and disappointment. That wasn’t fair, really; she was Rachel’s mother, and he did feel affection for her.

‘Yes, I dabble a bit.’

‘Waste of time, if you ask me.’ George, Rachel’s father, had lit one of his cigars that smelled like an overripe sewer and spread a mattress of blue smoke over the table. ‘Managed for centuries without them, why the sudden urge to put everything at the mercy of machines?’

Jerry chuckled. ‘You’re probably right.’ He fought down the impulse to cough, annoyed with himself. The smoke didn’t matter. ‘The Internet’s quite interesting, though. The possibilities for education are incredible.’

He caught Rachel’s reproving look and the casual, polite blankness in George’s eyes and shut up. If they weren’t interested, he had no right to impose on them.

After dinner he ran water in the sink but agreed with Rachel when she came into the kitchen that he should leave it to her and her mother, and joined George in the living room for a whisky. The older man argued the case for the new Mercedes over its BMW rival and Jerry contributed murmurs and short nasal exhalations of mirth while his thoughts ranged across the vistas of electronic space as they did until the early hours each morning, the exhilaration of unimagined possibilities spilling over into his dreams and shaping them so that he woke with an almost unbearable sense of purpose, that forced him to get up an hour before Rachel and caress the keyboard of his desktop like a master pianist.

‘Relegation for sure, unless they get their act together.’

At some point his father-in-law had turned the television on to a football match which Jerry knew was of crucial significance, and he sipped his drink and commented recklessly that the referee didn’t know what he was doing. From George’s backslapping tone he knew he had said the right thing, that the decision had favoured the wrong side, and he did not understand why his relief felt odd, unclean even.

He wondered why George had changed channels. The picture was of an empty room, with white walls and ceiling and floor, mildly interesting in its featurelessness. The camera was almost at floor level and swung this way and that, obviously the hand-held trick that had gone beyond a cliché long ago. Every now and again a pair of knees appeared at the bottom of the screen.

Help me… you must help me…

Jerry pulled himself upright in his chair and glanced sideways at the older man, who was biting his lower lip and muttering, ‘Come on, come on, pass it,’ before he slumped back in a snarl of clenched fists and mouthed oaths. Jerry looked back at the screen. All he saw was the room from the same ceaselessly moving perspective, and the voice came again, as if not from the television’s speakers but from the space between him and the screen.

You can help me.

I don’t have much longer.

Then the women came in with coffee and laughter and he joined in and when he peered at the screen again, the vividness of the red and blue men on the green of the field jabbed his eyes.

He locked the door of the Honda and swung his coat over one shoulder and walked to her, his face set in the expression of concern-tinged cheerfulness he had mastered long ago. He received and returned the kiss and followed her into the house, hanging the jacket on its peg and walking after her into the kitchen, where he perched on one of the two wooden stools at the small breakfast table and watched her at the stove.

Yes, not bad, the day.

Yes, the staff meeting had gone okay, a few protests about the forthcoming inspection but nothing major.

No, it had been the fifth-formers for two periods today, the sixth form was Wednesday.

How had her day been?

And on it went, he with his cup of tea, she half-turned towards him at the cooker, the saucepans simmering quietly and an undefinable aroma in the air.

Through the dinner of lasagna and salad, which he liked and told her he liked, he began to breathe more easily, letting the concern fade slowly from his eyes and his mouth; perhaps it wasn’t necessary. Television tonight, then, probably, the drama series they both enjoyed, and half an hour catching up with his e-mail, and then perhaps, at bed-time, a casual word, affectionately and humorously put, to the effect that she had seemed upset when he had come home and he was glad she was all right.

‘Samantha’s pregnant.’

He had been about to say something, the silence shading into discomfort, and he felt relief that she had spoken and then confusion at what she had said, at how he was supposed to react. She wasn’t looking at him and he had time to rummage through his closet of expressions and throw one on: the raised-eyebrow grin.

‘Really? That’s great.’ He gave it two seconds and followed up with, ‘When did she find out?’

‘Yesterday.’

She raised her head and he searched her eyes secretly. He couldn’t process what he saw there quickly enough so he said, boldly, ‘When’s she due?’

‘June, probably.’ She looked down at her plate. It was too much for him and he smiled and said, ‘Hm,’ and went on eating, wanting to flee, to bare his face to the cold dark autumn and run until the pain sawed his chest ragged.

Except that he didn’t. He wanted to be with Rachel, to comfort her, to make it right and to make her happy. Because he loved her.

He stood at the kitchen window, mug in hand, staring at the neat scrap of lawn with its spill of leaves at the border, at the stack of wooden boards and tiles that leant against the shed, raw materials for the kennel that had never been, for the dog that, he agreed with her, they could not afford. They had passed the evening as planned, side by side on the sofa, enjoying the drama on the television, except he had felt he was enjoying it more than she was; afterwards he had sat at his computer and read his mail and sent replies, while the sounds in the other room suggested she was on the telephone and he strained his ears desperately.

He made up his mind, and closed his eyes for a moment, and then went back into the living room where she was on the settee again, legs curled up under her. He sat beside her and smiled softly and said, ‘I’ve been thinking about it. For a while now, actually. Let’s have a baby.’

The room was white, a brilliant newly-washed white that extended into the farthest recesses where wall met ceiling. The man had covered every inch, moving his gaze as slowly as he could, seeking a sign that the purity of the wall and ceiling and floor was sullied, and failing. He had rubbed at the wall against which he sat with his head and the backs of his hands, and craned his head round to peer painfully at the wall out of the corner of his eye, searching for a smudge, an acknowledgement from the cold stone surface that he had marked it, that he existed, but the blankness remained.

The room was a cube, ten feet to a side, with a white door directly opposite him through which people came. He could see no handle on the door but the people who came always seemed to find one to let themselves out. He did not know how he could estimate the size of the room, or how he knew what a door was; no-one had ever taught him such things. He had been in the room as long as he could remember, and that was as far back as his infancy. In his childhood, he had run free in the room, and it had been larger then, much larger; it was not, he knew, merely his changed perspective as an adult that made it appear that the room had shrunk.

The man sat with his back pressed against the hardness of the wall and his knees drawn up before him. His knees were bony, and he knew the people would soon come in and change his colourless clothes for a set of a smaller size, the changing garb keeping pace with the shrivelling of his physique. His arms were stretched above him and away from him in a flattened Y shape, and they remained this way except when the people came to change his clothes, when he shook them and rubbed them and ignored the shouted orders to keep still until the manacles at the ends of the chains bolted into the wall were snapped into place around his wrists once more.

He could not remember when the chains had first been used to hold him. As a boy, he had been vaguely aware of their presence, two unobtrusive and therefore uninteresting features on the wall; but the wall, and the rest of the room, had not been as blank then, and he was unsure whether he imagined that it had been altogether a different colour, perhaps multicoloured, with vivid pictures the details of which eluded him now. It was as though he had been drugged for days, years even, so that his life had washed about him in a dimly-perceived and timeless sea until he had risen to full consciousness and found himself a prisoner, diminished and betrayed.

Yet he had not turned in on himself, displaying his throat for the people to cut. He pulled at the chains until his wrists were scraped raw; he yelled and cursed and spat in the faces of the people when they came in with food or clothing; he wrenched his failing body towards the half-open door whenever it opened, and earned abuse and slaps and blows sometimes. He did not know what lay beyond the door, although he had glimpsed things through it as a child that he had not understood but which had reassured him. As a man, he no longer derived any comfort from the thought of what was outside, and he knew therefore he must discover it.

At the first note of the bell the banks of protocol gave way to a shouting torrent of teenagers and Jerry went through the motions of dismissing the class, his voice louder than usual but unheeded. The last person to leave, a sullen owl-eyed girl called Zoe, passed his desk and he beamed at her; she stared back blankly and he moved a pile of exercise books from one side of his desk to another. The last double-period of the week, and he really felt he was getting somewhere with them, infecting them with his enthusiasm for the Tudors.

He had a free period and found Halford, the vice-principal, in the staff room. Jerry poured coffee and frowned, ‘They’re not as bad as I was told, actually. Form Six.’

Halford bobbed his eyebrows. ‘Then you’ve more patience than I have. I’d have achieved more talking to my reflection for forty minutes yesterday than standing up in front of that lot.’

Jerry laughed. ‘Thing is, I really want to make a difference, it’s why I went into teaching in the first place. If I can get just one of them interested, it’ll be worth it.’

‘Two or three of them need a good whack, that’d get them all interested,’ said Halford through cigarette smoke.

Jerry felt a tweak of annoyance. ‘Yep, can’t argue there,’ he grinned. Halford had been teaching fifteen years, knew what he was talking about.

Halford had his head in a newspaper and Jerry took out his diary for something to do and began paging. Rachel’s parents were coming up for the weekend, which he didn’t mind even though he had been planning to get his new website sorted out. There was always –

He had turned the page by the time he registered the words and he flipped back.

Help me.

The letters were large, in bold black ink, in the centre of the page. He had not written them. He was sure of it.

Rachel? One of his pupils?

Help me.

He riffled through the book but glimpsed nothing similar. He looked up but Halford was hidden behind his paper and seemed to have noticed nothing.

He was frightened.

The beatings were harder this time and the man shrank into himself as far as his manacled, exposed position allowed. There were kicks to his stomach, slaps to his cheeks, cuffs to his head, and he clenched his eyes and his jaws and endured. He endured because for the first time in as long as he could remember, his hope was real, not an abstract, free-floating concept but one rooted in the world. He had seen, in the broadest and most metaphorical sense of the word, another, who could help him, and he had communicated his desire for help in a manner which he did not begin to understand, but which had been effective. He did not know how the people who were beating him knew of this contact, and he did not care. What mattered to him was that he had achieved, that his actions had had an influence, and the knowledge was a spur to his rage and his joy. The blows came faster, and his tormentors screamed spittle at him, and he began to laugh, to himself at first, and then at them, in their faces, and although this drove their fury to heights and depths he had not experienced before, the resulting pain insulated him from fear and despair, the irony of which made him scorn them all the more.

Later, when they had gone in a throng of muttered contempt and revulsion, he slumped bloodied and exhausted against the wall, his eyes swollen almost shut and his mouth numb; but he did not sleep, even though his body screamed at him for the release of unconsciousness. The giddying sensation of his contact with the other was fresh in him, and he extended his awareness outwards instead of towards his core and let himself drift and probe…

‘Rachel tells us you’re into computers.’

Jerry topped up Dorothy’s wineglass. She was his mother-in-law, an austere sixty with arched artificial eyebrows and eyes that gleamed bitterness and disappointment. That wasn’t fair, really; she was Rachel’s mother, and he did feel affection for her.

‘Yes, I dabble a bit.’

‘Waste of time, if you ask me.’ George, Rachel’s father, had lit one of his cigars that smelled like an overripe sewer and spread a mattress of blue smoke over the table. ‘Managed for centuries without them, why the sudden urge to put everything at the mercy of machines?’

Jerry chuckled. ‘You’re probably right.’ He fought down the impulse to cough, annoyed with himself. The smoke didn’t matter. ‘The Internet’s quite interesting, though. The possibilities for education are incredible.’

He caught Rachel’s reproving look and the casual, polite blankness in George’s eyes and shut up. If they weren’t interested, he had no right to impose on them.

After dinner he ran water in the sink but agreed with Rachel when she came into the kitchen that he should leave it to her and her mother, and joined George in the living room for a whisky. The older man argued the case for the new Mercedes over its BMW rival and Jerry contributed murmurs and short nasal exhalations of mirth while his thoughts ranged across the vistas of electronic space as they did until the early hours each morning, the exhilaration of unimagined possibilities spilling over into his dreams and shaping them so that he woke with an almost unbearable sense of purpose, that forced him to get up an hour before Rachel and caress the keyboard of his desktop like a master pianist.

‘Relegation for sure, unless they get their act together.’

At some point his father-in-law had turned the television on to a football match which Jerry knew was of crucial significance, and he sipped his drink and commented recklessly that the referee didn’t know what he was doing. From George’s backslapping tone he knew he had said the right thing, that the decision had favoured the wrong side, and he did not understand why his relief felt odd, unclean even.

He wondered why George had changed channels. The picture was of an empty room, with white walls and ceiling and floor, mildly interesting in its featurelessness. The camera was almost at floor level and swung this way and that, obviously the hand-held trick that had gone beyond a cliché long ago. Every now and again a pair of knees appeared at the bottom of the screen.

Help me… you must help me…

Jerry pulled himself upright in his chair and glanced sideways at the older man, who was biting his lower lip and muttering, ‘Come on, come on, pass it,’ before he slumped back in a snarl of clenched fists and mouthed oaths. Jerry looked back at the screen. All he saw was the room from the same ceaselessly moving perspective, and the voice came again, as if not from the television’s speakers but from the space between him and the screen.

You can help me.

I don’t have much longer.

Then the women came in with coffee and laughter and he joined in and when he peered at the screen again, the vividness of the red and blue men on the green of the field jabbed his eyes.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Revenge of the limericks

‘Tis the summer! Time for barbecue,

Which Anti-B prefers not to do.

But his choice of food’s wrong!

He’d quickly change his song

Were mauve dinosaur on the menu.

Doc Maroon’s gone football-daft, a bit.

(How those ruffians curse, roar and spit!)

I predict, Gothic ended,

The next tale he’s intended

Will have us all dressed in football kit.

Closure, by the SafeTinspector,

Was in my dream last night. By heck! The

Lead roles were played by Brad

Pitt, Sting and Cheryl Ladd -

Sam Peckinpah was the director.

About his accent Kim's never lied;

There's nary a hint of a Scotch side.

So: what vocal inflections

(In our ‘Brits Abroad’ section)

Afflict Binty, and ProblemChildBride?

These are a bit laboured, and not nearly as good as they used to be. I have a headache and I need to lie down now. I'm sorry. Two 400 mg ibuprofen plus two Hot Lava Java coffees in the morning, they'll do the trick.

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

Like fishing with dynamite

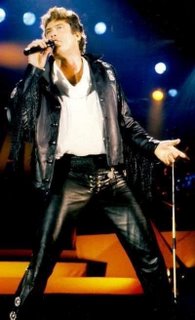

Taking potshots at David Hasselhoff is hackneyed, lazy and indicative of a peculiarly low sensibility. Nonetheless, I direct you to what has apparently been a long-running joke on Amazon: the growing collection of customer reviews of his Greatest Hits album. There are some gems here, and I’ve been laughing out loud for the last half hour. I have also lost thirty minutes of my life which I will never reclaim.

Still, it’s not as if the sad sod doesn’t deserve everything he gets. Check this out if you disagree.

Update!

Not 24 hours after I posted this, the link to the crucial second item is dead, and all the other Google links to the relevant clip lead to video screens which don't play!

Have I killed David Hasselhoff's career? Or - worse - killed HIM?*

Dave, man, if you're there, I loved Knight Rider when I was 12 and 13. That car and that soundtrack were brilliant. And I quite liked Baywatch as well... those plots, that tension! I watched with every sinew straining, the blood throbbing in my veins as only a 21-year-old's does. Watching the programme on Digital Versatile Disc over a decade later, I notice for the first time that the ladies were rather pretty too.

Sorry, Hoff, me old mucker, seriously. If by the remotest chance you're still out there, drop me an email some time. We'll have a beer and talk about how crap TV and music is nowadays. To make amends, I'll write you into my weblog somehow.

*or is there something wrong with my furrcken internet connection

Saturday, June 10, 2006

Why I am so great

This site has been averaging around nine hundred hits a day recently, so I thought I’d take this opportunity to introduce myself to the hordes of newcomers.

Hello, my name is Foot Eater, and welcome to my internet command node, The Fishwhacker Swindle? (The question mark is essential, by the way.) TFS? is a site dedicated to comedy, occasional short fiction, gruesomeness and incisive sociopolitical discussion, which last I haven’t got round to yet. This weblog might just save the world.

Here are ten reasons why I am wonderful.

1. I am famous. In the last month I have been linked to here and here. That second one is most gratifying as I have always really wanted to write about my true passion, Victorian houseware hardware, but have never felt ready to do so directly and have instead chosen to allude to it in the subtlest of ways. I’m pleased somebody has picked up on this.

2. I am handsome. Just look at my picture.

3. I have recently achieved something nobody else to my knowledge has ever managed, to wit, the Triple Fucklestop. (For a definition of fucklestop see here.) On Arlington Hynes’s site I brought the comment threads on three successive posts to a shuddering halt with the bone-grinding banality of my contributions. Gaze upon my works, ye amateurs, and despair.

4. I am the first person in the history of the human race to scoop the Blunt Cogs Smug Award for Best Character. I will always be the first, no matter who else wins in future. I am in a sense The Prime Character.

5. I am astoundingly modest.

6. I emerged the indisputable winner in my long-running public feud with El Barbudo. He is so cowed he’s afraid to comment on this site any more.

7. I am edgy, hip and happenin’, bro. Evidence? I own a cassette tape of Iggy Pop and the Stooges and I once listened to bits of a friend’s Dead Kennedys record. Furthermore, I sometimes wear shoes with no socks, and have bought clothes from TopMan.

8. I am man enough to walk away from a fight, secure in the knowledge that I am stronger in a moral sense than one who bellows “You’ll never get to black belt if you don’t start applying yourself.”

9. I know that when people criticise me they are being ironic.

10. I am very good at generating silly lists.

If anybody would like face-to-face coaching in achieving greatness, drop me an email, attaching a recent photo if possible.

Saturday, June 03, 2006

The Woodborn (part three)

‘It is in the wrists, and in the fingers.’

It was Kessler’s fourth day, his eighth lesson.

‘In the fingers, especially. The wrists are the leaps, the dips. The fingers are the pivots and the dancing.’

The old man lied to him. The wrists were the force of the hammer-blow to the nose, minimum energy channelled into the maximum pain, the fragmenting of bone and shearing of tissue, effortlessly shattering the integrity of the physical self, the discrepancy shocking and therefore undermining the more fundamental sense of wholeness. The wrists were the twisting of the ear, of the sex, the head on its axis. The fingers were the pressing of air from the trachea, the damming of the lifeblood in the thick vessels of the throat, the slow drawing back of the trigger into the release of noise and fire. Wrists, fingers, they were tools, not secrets, and utterly without meaning. He stood, uniformed in black and gold, beneath the reach of the branches, the twin bundles of wood and string twitching stupidly from his splayed hands and the ravaged ancient close against his back, the knotted claws gripping his forearms and the dry rotting-wood breath at his cheek, and the urge rushed from his belly like gorge: the urge to use the tools, to smash the old man and the ridiculous old puppets into splinters and to crumble the splinters into ash, then to bathe the village and its forest-father in a sea of fire. He cast his eyes up, imagining the branches drowned in flame, black char toppling and dissolving, the secret gone in the final laughter of the wind.

The elder released his arms as if sensing a change in him and he turned, gently, and the puppets were cast aside with a soft dry sound behind him and he took hold of the hard bulbs of the shoulders through their sack-wrapping and his face was close to the other’s; he could not see, through the hazy veils of the eyes, the shadows behind, but he knew from the stillness of the distorted old frame that he was seen, and was understood.

‘Do you see?’ he whispered. His arms shook the frail body. ‘Do you see what I must have?’

The voice was as low as a wind trapped for aeons in the forest: ‘Yes.’

He released, stepped away, not afraid. He stood erect, his hands by his sides.

‘Show me now.’

Within an hour, the old man had reached the tree. The moon, its sheet dispersed through the sieve of the leaves and branches into a silver rain, had at first allowed him to step over the exposed roots and moss-hugged fallen trunks, to prise his way between the snarl of arms and vines. As he had sunk deeper, the rawness had engulfed him so that the light had retreated, beaten, and once the false guide of a forest-creature’s eyes, flat green winking discs directly before him, had tricked him over the bank of a small gully so that he had sprawled with a gasp, and lain with his mouth pressed into trickling sweet earth, the rushing in his brow seeking the rhythms of the enclosing dark.

He stood before the tree, its brawny torso splashed with a torrent of white from a space in the canopy far above. The tree was father and mother, its great branches fisting upwards from the puckered wrinkles of the birth-scars near its base. The older and lower wounds, the places from which he had hacked the branches from which he had carved Tomas, were furred with moss; the newer Frieda-cuts were still angry and blistered with dried sap. Twenty years ago, he had been midwife to Tomas; ten years later he had brought him a mate; and the parent was slow to forget.

He knelt before the mighty base, for the tree was to him as fifty generations were to the innocents who clustered about him daily in mute reverence. He knelt, the pain of the hard damp knots of stone and root pinching his bony knees, and above the soft murmur of the forest’s wind and the teeming night noises of its offspring, he began his confession.

I have given you to another.

I have taken what you have given and I have soiled it, spat on it.

He did not say, I have protected your children, for he had taken those children by force. He did not bury his face into the forest floor, rage into the night, beg the parent to maim him, twist the life from him. Excuse, self-abasement, had no place in the presence of the dreadful wisdom of the parent.

By unspoken command his head was raised and, neck craned, he gazed at the bole above, its coat of cold pale fire-light glimmering. The parent stared down at him, at the being at its foot who had stabbed and rent it, ripping the two tiny doll-bodies from its flesh, and he thought it no more felt the absence of its spawn than the ocean resented a child’s scoop from its rim. The removal had extended its grasp, no more; had spread the reach of its power. And he knew then that the power remained that of the parent, could not be transferred, and that he had given nothing to the man.

This time, as he made his way back, the light remained, his footfalls true and effortless; and once, when he paused to slow his breath, he felt the glitter of tears on his face.

Noon, and the sun was his spotlight, its bright stare proper for the occasion, yesterday’s milk-filter gone. Kessler’s tunic shone blackly, the sleeves rolled up. His wife had shone the buttons well: a favourite dress, a smile of affection, would be her rewards, were owed to her.

The tableau was imbalanced: before him, the perfect chaotic spontaneity of the children, thirty again, in their half-circle, the force of their expressions combining a few feet ahead of them and channelled at him, no surprise in the solemn faces, no wonder at the unfamiliar scene. But to his left, wavering at the interface between illusion and invisibility, the brittle figure, hands clasped in front of its scrawny sack-clad belly, and he fancied its eyes were on the crates at his feet.

In the bright silence, he reached into the box at his right hand and clasped the jointed cross and lifted the girl-puppet into the light. He had mastered the technique of watching the puppet with one eye, his other on his audience, and he was looking for a ripple of surprise. He was disappointed to see none. Perhaps the old man himself had sometimes begun stories with the girl-puppet rather than her mate. His fingers felt more natural, more at ease, manipulating this one.

‘Here I am, all alone, with nobody to play with.’

He felt a flicker of satisfaction as he heard his voice, normally a carefully modulated tenor, now raised perfectly into a little girl’s plaintive murmur. His technique was expert, the wooden hands deftly manoeuvred so that they appeared to be clasped before her in dejection. He breathed, as the old man had taught him to breathe, drawing the vastness of the forest behind into his chest. His scorn and disbelief, which had at first threatened to deafen and blind him to the elder’s instruction, he had learned to suspend: strategy was all, for now, until he had made the power his, and then the pathetic superstitions would be tossed aside, broken and dead.

It was not until the boy-puppet, Tomas (as he was now called; the names would need to be changed) stood and jigged beside its companion that he became aware of how completely he had given himself to the ‘strategy’, for he realised that he had not been watching his audience with one eye, had not, in fact, been conscious of seeing anything at all. He spoke and his fingers and his wrists played, and he saw that the children’s gazes were on the puppets. He scanned the faces quickly, the shadow of an impression flitting almost beyond the reach of his awareness until he grasped and identified it. The children’s eyes were not moving to follow the bobbings and weavings of the wooden figures; seemed, in fact, to be focused beyond the puppets, beyond him.

He was gripped by an urge to look behind him at the forest and he resisted, staring instead at the dancing figures. Their motion drew his gaze, distorted the perspective so that the puppets appeared taller, their heads now at the level of his waist. Then he realised his hands had stopped moving.

From behind there was an awful pressure on his back, and he felt himself impelled forward towards the skipping marionettes. He could focus on them now without lowering his gaze from the horizontal, and as the round wooden skulls swivelled and the painted grins faced him, he saw the children, risen to their feet and grown huge, approach.

His hands flailed at the sky, his feet jerking and scrabbling in the dust until he was grasping nothing yet was somehow lifted from the dirt floor, his head bobbing so that his vision trembled. He opened his mouth to shout, found his lips clamped shut and curved downwards obscenely at the corners, a parody of tragedy between the dual gaieties of Frieda and Tomas. He tried to blink, could not: a not-face to accompany his not-limbs. He wanted to look above him and, when he felt a tug, let his head loll back.

From his hands, from his head, strings converged in a foreshortened steeple to a wooden cross around the centre of which curled the gnarled knuckles of an enormous hand. The cross and the hand obscured most of the old man’s face, one yellow eye visible peering down across the wildness of his beard. A twitch of the hand and he felt his head bounce forward again. Knees and skirts and ragged small shoes hovered before his gaze, and were replaced gradually by giant faces as the children crouched to look at him. He found it difficult to focus on any single point, his movements were becoming more rapid, more complex, but nevertheless he picked out one face: it was a little girl, her tiny mouth and huge eyes solemn, a staff of wood grasped in both hands across her lap.

He could not blink, he could not move his limbs, he could no longer even feel the movements at his joints, his awareness shrunk to the field of vision directly ahead of him and to a vague sense of self within the confines of his tiny head; a self so purely passive he marvelled at it. He had known passionately all his life that this state was achievable, had held on to this belief in the face of defiance and ridicule; how delightful, how ironic, that he, who had striven to cultivate it in others, had now attained it himself!

He found himself facing the girl-puppet, Frieda, and the way they whirled and dipped in tandem made him realise he was dancing with her. Her face, so crass and gaudy before, was beautiful, he saw now that he was close. They were spinning so fast that the wood was no longer behind but formed the walls of a tunnel around them, and he was dimly aware that others had drawn near, the adult villagers and even, he fancied for an instant, his wife, his son. The old man, the children, the forest, were his masters, immense and absolute, best ignored: for here was Frieda, and Tomas who had joined the dance and smiled and nodded at him, and here, among his new companions, he felt at last that he truly belonged.

Finis

It was Kessler’s fourth day, his eighth lesson.

‘In the fingers, especially. The wrists are the leaps, the dips. The fingers are the pivots and the dancing.’

The old man lied to him. The wrists were the force of the hammer-blow to the nose, minimum energy channelled into the maximum pain, the fragmenting of bone and shearing of tissue, effortlessly shattering the integrity of the physical self, the discrepancy shocking and therefore undermining the more fundamental sense of wholeness. The wrists were the twisting of the ear, of the sex, the head on its axis. The fingers were the pressing of air from the trachea, the damming of the lifeblood in the thick vessels of the throat, the slow drawing back of the trigger into the release of noise and fire. Wrists, fingers, they were tools, not secrets, and utterly without meaning. He stood, uniformed in black and gold, beneath the reach of the branches, the twin bundles of wood and string twitching stupidly from his splayed hands and the ravaged ancient close against his back, the knotted claws gripping his forearms and the dry rotting-wood breath at his cheek, and the urge rushed from his belly like gorge: the urge to use the tools, to smash the old man and the ridiculous old puppets into splinters and to crumble the splinters into ash, then to bathe the village and its forest-father in a sea of fire. He cast his eyes up, imagining the branches drowned in flame, black char toppling and dissolving, the secret gone in the final laughter of the wind.

The elder released his arms as if sensing a change in him and he turned, gently, and the puppets were cast aside with a soft dry sound behind him and he took hold of the hard bulbs of the shoulders through their sack-wrapping and his face was close to the other’s; he could not see, through the hazy veils of the eyes, the shadows behind, but he knew from the stillness of the distorted old frame that he was seen, and was understood.

‘Do you see?’ he whispered. His arms shook the frail body. ‘Do you see what I must have?’

The voice was as low as a wind trapped for aeons in the forest: ‘Yes.’

He released, stepped away, not afraid. He stood erect, his hands by his sides.

‘Show me now.’

Within an hour, the old man had reached the tree. The moon, its sheet dispersed through the sieve of the leaves and branches into a silver rain, had at first allowed him to step over the exposed roots and moss-hugged fallen trunks, to prise his way between the snarl of arms and vines. As he had sunk deeper, the rawness had engulfed him so that the light had retreated, beaten, and once the false guide of a forest-creature’s eyes, flat green winking discs directly before him, had tricked him over the bank of a small gully so that he had sprawled with a gasp, and lain with his mouth pressed into trickling sweet earth, the rushing in his brow seeking the rhythms of the enclosing dark.

He stood before the tree, its brawny torso splashed with a torrent of white from a space in the canopy far above. The tree was father and mother, its great branches fisting upwards from the puckered wrinkles of the birth-scars near its base. The older and lower wounds, the places from which he had hacked the branches from which he had carved Tomas, were furred with moss; the newer Frieda-cuts were still angry and blistered with dried sap. Twenty years ago, he had been midwife to Tomas; ten years later he had brought him a mate; and the parent was slow to forget.

He knelt before the mighty base, for the tree was to him as fifty generations were to the innocents who clustered about him daily in mute reverence. He knelt, the pain of the hard damp knots of stone and root pinching his bony knees, and above the soft murmur of the forest’s wind and the teeming night noises of its offspring, he began his confession.

I have given you to another.

I have taken what you have given and I have soiled it, spat on it.