Wednesday, May 31, 2006

The Woodborn (part two)

His wife, in the mirror, made a small gesture with her hand, her eyes on his throat. Kessler saw and fingered the knot of the tie. Long ago, she would have touched it herself. It had not been long before she had learned.

At the table, she was silent. He asked why.

‘A letter came this morning. From Michael.’

Long ago, she would have replied: nothing. She had learned.

‘Let me see it.’

Their son had obtained the results of his examinations. He had achieved distinctions in the sciences and mathematics. Kessler folded the letter. His wife watched his eyes.

‘It qualifies him. He will be accepted for engineering,’ she said.

‘Would. He would be accepted, were he to apply.’ He was irritated with himself. He had assumed discussion of the subject had ended months earlier. He had not the time, now, to correct his error. He stood, and was surprised when she rose with him. Her eyes met his, slipped, rested on his cheek.

‘He wants it more than anything else.’

Later, he would finish it. He would explain again that their son would enter the Academy, that he would excel and be marked early on as an officer, that he would continue his father’s work in the provinces. He would explain the importance of the military way, its place at all levels in the new order, and she would understand the reference to her behaviour this morning, and this time she would not forget. Now, he had other work to do.

He felt her eyes dropping from his back, and walked out to his car without looking at the guards on either side of the door of his house. His driver was waiting behind the wheel. The journey to the headquarters was twenty minutes of dust and machinery clatter, trucks lumbering aside in clumsy respect as the driver steered a smooth path through the streets. From the back seat Kessler watched three squat vehicles surrounded by shouting men haul a giant stone statue erect, and the men cheered with a single voice as they stared up at it. He turned to look at the statue through the rear window as the car passed; it was of a man in general’s uniform, one hand on the sword at his belt, the other outstretched, palm down, shielding the people gathered at the feet. As the scene dwindled, others were coming out of the houses, women and children and the old, to stand at the base of the statue and leap and laugh beneath its reach.

He spent half an hour at the headquarters and then he was in the car once more, a personnel carrier behind and two smaller vehicles ahead. His lieutenant, Veneman, sat in front beside the driver, his head turning to the side in a single cog-wheel movement each time Kessler spoke. Soon the city was behind them, crowned with a fog of dust that scattered the pale eastern sun. Ahead, the road dropped steeply into tree-shadow and the sharp sap of pine cut through the diesel stink.

The village was five kilometres down a dirt track that had been worn down by feet and wheels. The track widened into the village centre, a square bordered by ancient stone-walled houses, a church to the right, what appeared to be a school building on the left. In the middle of the square was a fountain, a statuette of a woman holding a pitcher on her shoulder from which water trickled into the fountain’s basin. Beyond the buildings was the forest, as though the village had gently nudged the trees aside to ease a space for itself. Nine or ten people stood around the square, women with pails and bundles, old men talking over pipes. Far away, a bell rang, two notes repeated over and over and slightly irregularly as though it were being rung by hand, the sound dissipating into the trees.

Kessler motioned to the driver and the man flashed his lights and the two cars in front stopped. He sat in the back and waited for the driver to open his door, watching the people who stood around the fountain. They looked at the vehicles, their eyes incurious, and the men sucked at the stems of their pipes and the women hefted their pails but did not lower them. Lessons there were, and to be taught quickly. Outside, he gave his orders briefly, and there was fast motion. He watched as the gate of the school building on the left bulged and then flung out a spume of children, not raucous but solemn, drab in colour as they filed across the central cobbled area and down the road away from him. Few of them glanced at him, at the cars.

Kessler checked the sharpness of his collar with his fingers and the cold holstered metal at his belt and set off after the children, and when the lieutenant Veneman stepped to his side he murmured ‘No’ and the man fell back. He kept up, though the line before him moved quickly, and when after half a mile it slowed he steadied his pace so that he hung still further in the rear. The village had almost ended by now, the trees sucking in the road so that it was little more than a sand path. The stone fronts of lone houses peered between the trunks.

The children, perhaps thirty in number, ordered themselves spontaneously, the tallest standing at the back, the smaller ones squatting in the dust in a ragged semicircle before a tight twist of thick boles. At the base of the trees were two wooden crates, three feet high and as broad, their sides carved with leaping figures. The children had been voiceless throughout the journey and were silent now; they did not fidget, they did not laugh or squabble.

A man stepped out from between the trees. He was old, his spine stooped, his hair and beard sparse and drifting as a web. Kessler could see nothing of his eyes, but the raddled cords of the brown arms that protruded from the filth-rags revealed a strength which spread down to the spindled clicking fingers. The man stopped at the boxes and raised the top off one, laying it down carefully and then with equal gentleness grasping into the depths and lifting out a twitching elongated bundle of wood and string and paint. The man held the puppet high and as he reached with his other hand into the box the tangle from his first hand began to take on form, thickening and jerking so that four appendages grew and tested themselves and all at once there were two grinning impish beings, their clothes and their noses and ears ridiculous and compelling, and a sigh of recognition riffled through the watching group.

The old man was speaking, his voice high and keening, rising to an absurd falsetto to represent the speech of the female marionette, slipping to a tenor for the male. Kessler was aware of the vague shape of a story but he paid little attention to it, less still to the movement of the characters in response to the rippling of the ancient fingers. His eyes slipped across the unmoving audience, now settling on a wide-mouthed profile, now resting on the back of a shorn head which by its stillness communicated fascination, rapture. With the frozen tableau before him and the flickering of movement and sound at the periphery, he felt the slow swell within him until he could no longer contain himself and stepped forward so that the tips of his boots were inches from the cusp of the half-circle, a bare brown back exposed where the child’s shirt had rucked up out of the tattered trousers. He was no longer hidden, no longer in the background, and the puppets continued their dance, and their master’s eyes were closed as his hands glided and his lips spilled their legend. He stood, erect, in the sharp sheen of his leather and keen-pressed cloth, and the children’s heads did not move at the shuffle of his boots in the dust.

The elder stood, his stoop gone, the puppets upright but motionless, his eyes closed, and the black and brown and gold heads before him were still also, and through the silence the whisper of the wind started in the engulfing forest and then died, as though cowed.

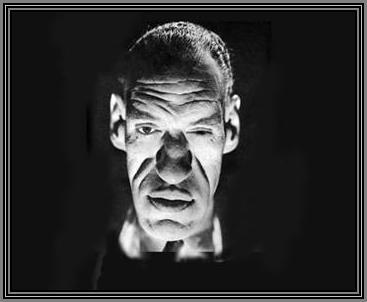

The eyes opened and he gazed into them, and there he saw what he had not seen in the eyes of the man he had shot in the last village, in those of the pathetic hundreds who had raged and smirked and eventually shrieked and bled at his feet. He saw, in the yellow stare, what he himself felt, what the ancient possessed, and there was something else he felt, which he did not see, and the rage rose in him and he said gently: ‘Good morning. I am Colonel Kessler.’

‘Who are you.’

The tone soft, the words pared off like slivers from a block. He gazed at the bright yellow and red and green of the ribbons at the left breast. He thought he should look at the eyes, but he was old.

‘Who are you.’

He did not lift his eyes. ‘I have told you my name.’

‘Yes. I am not asking for your name. I am asking who you are.’

I am an old man. I am a villager. I am a puppeteer. ‘I don’t understand.’

There were three in the room, three that creaked and shone when they moved, but the man with the ribbons was before him and was the master. The man with the ribbons, the colours, stood at the other side of the desk at which he was sitting.

‘The children came to you, immediately.’

He said nothing.

‘Do they come to you every day?’

This, he could answer. ‘Yes. Those who -’

Silence, and he knew he would have to end it.

‘Those who are permitted. By their parents.’ Then he looked up at the face, but its sharpness was painful and he spoke quickly so that he could drop his gaze again. ‘I don’t know who they are. I don’t know their names, or who their parents are. I don’t know which children are forbidden to come.’

‘How often do they come.’

‘Twice a day. Noon and dusk.’

It continued: is it always the same story, do you have other puppets, do you talk to the children directly. His third no and he peered up quickly again, afraid that his replies would be interpreted as insolent, but the eyes on him were steady. He dared to hold the gaze, saw the mouth stretched thin and taut across small neat teeth, fancied he could taste the sour tang of the man’s breath in his nostrils. He stared at the eyes and waited for the hate, the contempt. He saw fascination, eagerness, even.

Emboldened, he murmured, ‘Please don’t punish them. The parents, either… They don’t know…’

The arms were braced on the table, the face closer, and he felt the eyes. Beyond, unfocused, the other two creaked, coughed. He tried to concentrate on them, the non-essential, the banal, but the eyes burned and probed and he suddenly slumped forward on the desk and gave himself up to the engulfing presence above and before him and the thin lips opened with a tiny dry husk and all he could see were the ribbons, green and gold as the forest as the voice hissed: ‘The Renewal requires it. You will show me the secret of the puppets.’

For a minute, he was gone, bobbing away on a gentle current from the tableau of interrogators, and he was laughing, at the child-awe of the tone, the hush of the phrase: The Secret of the Puppets. The earnest upturned face, pink and scrubbed free of smudges, above the fierce innocent important ribbons, beckoned to his compassion, his passion, his desire to fill with his wisdom, and he smiled because it would be easy to speak, easy and therefore worthless; with his hands he lifted Tomas and Frieda from their boxes and with his fingers he gave them life, and as they soared and danced he pulled to the side, away from the forest, he was too close to the forest because the branches were grabbing at him and wrenching and he could not go with them, had not finished.

His fingers flicked a signal and the sergeant let go of the man’s ear and the twisted body jolted back into the chair, the lids blinking slowly. Kessler leaned his forearms on the table and brought his face close so that the eyes swam at him through their egg-film.

‘You will stay focused.’

The tip of the tongue probed greyly at the withered lips. Kessler reached out and gently tilted the head back with his fingertips; it was less easy for the eyes to avoid his.

‘You say, there is no secret.’

The eyes hovered beyond his, in their tortoise hoods. The face was a gnarled trunk of ash that sprouted matted grey moss. The mouth-cleft split and writhed soundlessly.

‘But the children came to you, today. They came to you and I was there, with all this.’ He flipped a hand at the man beside him. ‘All this, and they watched you.’

Movement, then, a lifting of the eyes, rather than the head, and Kessler grasped for the meaning, pride, was it, no, that was too obvious, and then he saw it and was enraged and grabbed the ancient tree-man, seized his foul splintery scrag-hair and jerked him up out of the chair, and beyond the flicker of pain the expression remained. He twisted the man from behind the table and toward the door, his sergeant already wrenching the lid off the first box, the second, and flinging the limp clacking tangles of wood and string through the open doorway to sprawl in the dust and stone.

His face was close to the elder’s now and he noted the first twitch of doubt. The triumph soared within him as he nodded to the sergeant, unsmiling. The arc of gasoline glittered and the wood and string lay stinking and anointed in the sun.

‘I will.’

He nodded again, and in the sergeant’s hand the rasp of the match spat a tiny cone of fire.

He felt the elder sink and lowered his arm, controlling the movement so that the creaking tree-man, the nothing, knelt with arms loose, held upright by his hair, and through the lank matted swathe a sob, a murmur.

‘I will show you the secret.’

Monday, May 29, 2006

Mailbag roundup

Running a comedic weblog is not without its hazardous side. I’ve received a few letters in the last week which border on the nasty. This one, for instance:

Dear F Eater

Your lack of a cohesive identity would be hilarious were it not so tragic. Like so many blogs spawned by that of the inimitable Harry Hutton, you started out no doubt intending to post pithy contributions every few days, incorporating humorous and occasionally surreal observations on life and in the process amassing a fanatical fan base of witty, erudite followers who lap up your every ejaculation. Again like so many others, you appear to have run out of steam once your initial creativity burned itself out, and now resort to disparate postings of wildly uneven quality with no trace of a unifying theme. Those comments which are appended to your posts are by people who feel sorry for you and who feel obliged to reciprocate as you continue desperately to comment on their own sites, toadying lickspittle that you are.

Yours sincerely

XXXXXXXXXXXXXX

[I’ve censored the name on legal advice but a quick click on each of the links on my list will make it obvious who sent this]

To which I can only reply: ‘Initial creativity’? I started this blog in the middle of a creative slump, you hound, so you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Somebody calling itself Lord Byron’s Crapper writes:

Dear Mr Food Eater

Why do you persist with posting those stories of yours? A few people skim through them out of a sense of duty but really, they’re just a waste of valuable bandwidth, aren’t they? Do you know how many starving children in the Third World could be fed in the time it takes to read your tortuously-constructed prose?

While this one, written in green ink, arrived yesterday:

Dear Eater

Your pedantry marks you out as somebody with very little ultimately to say, but quite ready to criticise others who take the time and trouble to offer their thoughts (ha! I spelled ‘their’ correctly, as ‘their’ and not ‘there’ or ‘they’re’, so don’t even go there) for the web community to read. Having said that, anyone would be mad if they [sic] were bothered by your opinion anyway. I’m not.

Regards,

The Anti-Pedant

My reply, could I be I bothered to send one, would point out the dangling participle in the penultimate sentence.

Finally, in what’s been a grim week, Fish Food opined:

dear foot eater

next youll be making a really self pitying navel gazing post about the trials of being a blogger in order to build up a critical mass of comments like you did when you disappeared for a couple of weeks. you attention seeking fraud you.

Fish Food, you’re hired. Can you start today?

Dear F Eater

Your lack of a cohesive identity would be hilarious were it not so tragic. Like so many blogs spawned by that of the inimitable Harry Hutton, you started out no doubt intending to post pithy contributions every few days, incorporating humorous and occasionally surreal observations on life and in the process amassing a fanatical fan base of witty, erudite followers who lap up your every ejaculation. Again like so many others, you appear to have run out of steam once your initial creativity burned itself out, and now resort to disparate postings of wildly uneven quality with no trace of a unifying theme. Those comments which are appended to your posts are by people who feel sorry for you and who feel obliged to reciprocate as you continue desperately to comment on their own sites, toadying lickspittle that you are.

Yours sincerely

XXXXXXXXXXXXXX

[I’ve censored the name on legal advice but a quick click on each of the links on my list will make it obvious who sent this]

To which I can only reply: ‘Initial creativity’? I started this blog in the middle of a creative slump, you hound, so you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Somebody calling itself Lord Byron’s Crapper writes:

Dear Mr Food Eater

Why do you persist with posting those stories of yours? A few people skim through them out of a sense of duty but really, they’re just a waste of valuable bandwidth, aren’t they? Do you know how many starving children in the Third World could be fed in the time it takes to read your tortuously-constructed prose?

While this one, written in green ink, arrived yesterday:

Dear Eater

Your pedantry marks you out as somebody with very little ultimately to say, but quite ready to criticise others who take the time and trouble to offer their thoughts (ha! I spelled ‘their’ correctly, as ‘their’ and not ‘there’ or ‘they’re’, so don’t even go there) for the web community to read. Having said that, anyone would be mad if they [sic] were bothered by your opinion anyway. I’m not.

Regards,

The Anti-Pedant

My reply, could I be I bothered to send one, would point out the dangling participle in the penultimate sentence.

Finally, in what’s been a grim week, Fish Food opined:

dear foot eater

next youll be making a really self pitying navel gazing post about the trials of being a blogger in order to build up a critical mass of comments like you did when you disappeared for a couple of weeks. you attention seeking fraud you.

Fish Food, you’re hired. Can you start today?

Saturday, May 27, 2006

The Woodborn (part one)

He had opened the first box and was lifting Tomas out, taking care not to entangle the limbs in the strings, when he saw the little girl approaching through the pale sunlit dust. He stopped and watched as she strode towards him, wearing the shabby blue dress, the solemn pinched expression, the staff of bare smooth wood hanging from her fist. She stopped before him, staring at Tomas, and he smiled.

‘Good morning.’

He lifted the wooden cross above Tomas so that the puppet sprang to life, and tilted his wrist so that it raised its arm in greeting. ‘Tomas says hello.’

She raised a small fist in response. Tomas was clad in a gaudy billowing blouse and trousers with white and scarlet stripes, and he placed his hands behind his enormous ears and grinned at her, bending his knees and kicking his pointed green shoes up in turn. The puncture of her mouth grew into a line, and she clapped her hands and her eyes widened at the old man. He felt the pain of dawn on frosted glass.

Still working Tomas with his right hand, he reached across and tipped the lid off the second box with his left and reached in and brought out Frieda. Her bulb cheeks and sausage nose could make her Tomas’s sister or mother or daughter; often she was his wife or sweetheart. Today he had dressed her in a yellow satin tunic and a skirt like a bell, that would flare as she twirled. He had hoped the little girl would come.

There was a wooden stool that he kept varnished, but the little girl never sat. She stood with her feet together, hands clasped, serious again. He began the tale, shortening and simplifying it, hiding each character in turn behind a box while the other took the centre. He told of Frieda, the little girl who lived with her woodcutter father and drew water every morning from the stream in the woods, content to help her father but without joy in her life; of Tomas, the boy with music in his heart but also loneliness; of Tomas’s long hours staring at himself in the surface of the stream in the woods, wishing for a different face to look back at him, until he lost his balance and fell into the water and was washed for miles until Frieda pulled him out. The old man chose high sad tones for Frieda, deepened his natural voice into a duck-like jabber for Tomas which had the little girl shrieking with glee. When he tumbled Tomas into a chaos of flailing limbs for the drowning scene, his tone rose until he realised he was shouting and the girl looked so frightened he thought she would wail; the rescue was done so deftly, the girl-puppet rushing out from behind the box and drawing attention away from his right hand which gripped Tomas’s strings and jerked him to a stop, that the little girl gasped.

He made Tomas’s splutters and panting die slowly, and paused deliberately, enjoying the annoyance this always provoked in his audience, the impatience for resolution. The little girl had not seen this tale before, and she stared from puppet to puppet to their master, her eyes begging him not to let it be finished.

‘Do you know what they did then?’ he asked gently. She shook her head, breathing through her mouth as if trying to keep silent. He leaned forward, laughing inside as she did the same, craning her eyes and ears towards the secret.

‘They danced.’

A faint line separated her brows as she moved her lips around the taste of the word, and he felt the sting in his eyes and his throat and thought: she doesn’t know it. He whispered to the question in her gaze, ‘This,’ and it began in his head with a great organ flourish, it was always an organ, no matter what the tune, and the chords were major, starting slowly and softly and made physical in the turning of the two puppets to face one another and the shy reaching of their arms for each other, and building so that he closed his eyes and summoned the orchestra from far within him and unleashed it through the arms and legs of string and wood and cloth until he could hear the little girl far below him screaming and stamping in delight and could see through his closed lids the whirling marionettes, young and alive and dying.

The ride had not been a good one. Twice the driver had had to brake and swerve, the first time to avoid a pothole that would have certainly damaged the car’s axle, the second to swing clear of a dark shape in the centre of the road over which a sack had been carelessly flung. The second time the driver had not been so quick, and the left front wheel had rocked over the corpse’s head and burst it.

Kessler stepped from the car and watched the black uniforms slot themselves rapidly into a single row, nineteen in all. The lieutenant strode towards him and snapped a salute.

‘Colonel. Eternal glory to the Renewal.’

‘Secured?’

‘Yes, sir. The entire area.’

He walked down the line, not looking at the men, feeling them stiffen as he passed each one. Beyond them, mounds of smoke fumbled across the wreckage of rooftops, dragged behind a tired wind. By the side of the road, in a gravel half-moon in front of an inn of some kind, about thirty people lay face down in silence, hands clasped behind their heads, soldiers standing over them. He stopped and jerked his head. The soldiers shouted and jabbed with their rifles and the people began to pull themselves to their feet. A low whisper started and there was brushing of dust off clothes and the soldiers yelled again and the hands went behind the heads.

Kessler examined the group. Perhaps a third were women. The faces were pale and sullen, glowering through streaky dirt. Most were young, in their twenties or thirties, though there were three or four grey heads. It was one of these that he needed.

He selected a man standing close to a younger woman, and muttered to the lieutenant. A soldier moved and the man stepped forward and apart, the woman making a soft cry and her hands moving to her mouth, and he knew he had chosen well.

In the inn, the man sat, his rough veined hands clasped before him and the hate-lust in his shadowed eyes. Kessler stood over him and gazed at the ceiling with its black stoic beams. He watched the beams for a long time, and then dropped his eyes, not to the man but to the soldier to his right, crisp and pink-shaven, and said, ‘Where is the base.’

There was silence, and from the man on the rim of his vision, not feigned incomprehension, not outrage, but hate, simple and honest and direct. It was not enough.

A nod to the lieutenant at the door and the door opened and through the stillness, there were shouts and a crash and then the punctuation of silence. The door slammed open and the body was flung with a wet smack to sprawl twist-necked on the floor to the man’s left.

Kessler watched the face. He spoke rapidly, with the detachment of authority. The lieutenant had briefed him quickly, and he had listened.

‘This is your eldest daughter, Sara. You have a son, Jonah, aged thirteen, and a daughter, Faye, seven. Where is the base.’

The eyes were seeking his now, yellow, even the irises, and the hate was there but small, like a child’s fist, and within the huge darkness of the pupils he saw the man, bent and crawling in a void with his light shattered and gone and his, Kessler’s, face luminous and swelling before him.

He had chosen well.

The base was twenty kilometres away, in a dismal country slope of firs and logs and a river, secret but indefensible, pathetic. Ground troops, then, half a day and it would be over, wiped like a smudge from a glass. He watched the man while the lieutenant made notes and spoke sharp quick orders into his hand. The man did not look at the body, his blue-cabled hands still, the flesh of his face wondering vaguely why it lagged behind him in the death journey. Kessler stepped forward and pushed the end of a cigarette between the man’s lips and lit it, and still the hands did not move, the slow intake and exhalation of breath dragging out the gnarl of ash. Kessler clipped open the holster at his belt and drew his pistol and shot the man in the head, and the hand on the floor hurled wide from the body twitched at him before curling.

They had come to the old man one evening after the sun had dragged the thin autumn light beyond the pines, tapping on the door of his hut, and he had opened the door as he would have if they had hammered with their fists. Four of them, each young, each with the grim heroic certainty in his brow, and the fear apparent in a shift of the eyes or a too-frequent settling of weight from one foot to the other.

‘You do not realise the influence you have.’

‘You can keep the spirit of the Resistance alive here.’

‘You have an obligation to the children, to all of us. You do not exist alone.’

They had spoken of subtlety, of a message so ghost-like it would be like the pulse of blood in the viewers’ veins, unconscious yet vital. One of them had pulled a grubby sheaf from his pocket and thrust it at him with the awkwardness of the shy. It had been a script, written as dialogue in the manner of a play, full of parenthetical grimaces and sneers for the actors, and concerning the exploits of Dick and Tor and their building of a ship using the slave-labour of the village which they ruled, the sabotage of the ship by the villagers and its sinking. Dick and Tor’s ship. Dictatorship. It had been years since he had wept, but he had wanted to weep as he handed the sheaf back to the young man.

To their hurt angry stares, as he had closed the door, he had said simply, ‘I make my puppets dance. That’s all they need to see,’ and he had watched them through the crack of night and forest, looking for a blink of understanding, seeing nothing but despair and bewilderment. He had gone to the back of the tiny hut and opened the boxes and Tomas and Frieda had clambered to life, grinning their wooden innocence at him, and as they had started a gentle waltz he saw behind his eyes Tomas in mud-smeared victory holding aloft a bloody bayonet, and Frieda marching up a staircase of skulls with the troop of children behind her, the little girl at the head, and he knew that he would rather cut the life from their strings and see them sagged and silent.

Twenty years ago he had come to the village, and the stories he had told with his wrists and his fingers had altered little, as the children had grown and drifted away and a new generation had come to him. He had watched them, sifting through the reactions in the tiny faces, making Tomas and Frieda respond until the cells of the audience had over weeks, months, knitted together into a breathing tissue. Then five years ago, the change had come in a chill raw wind that had crawled across the land through the village, so that the new group of children had come to him blank and stunted, the words from their mouths no longer wondrous and new but withered and as coarse and unquestioned as the dissolving of the old hard bread in their bellies. He had sat alone by the guttering table-lamp, his new duty a majestic horse-backed pioneer in his thoughts, a tight mocking horror in his stomach. In the years since, he had listened to the whispers creeping from the trees, the hissed rage at the apathy and fear of the village which had become a snarl that retched out crude pamphlets in the streets shrieking warnings about the slaughter of collaborators. He had sat in the desolation of aloneness and had come to welcome it, for it allowed him nowhere to turn for distraction, forced his focus on Tomas and Frieda and his audience, and he had played and danced the puppets and for a few hours each day, he felt drunk on the simple cleanness of truth.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Take them, God, please

Really scraped the barrel with that last post, didn’t I? I’ve only just got back so haven’t read any of the comments yet, but I expect they’re all abusive and rightly so.

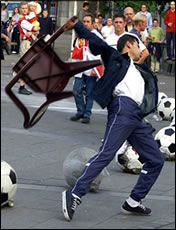

I was looking forward to posting about the delights of Paris – the Champs Elysee, the Louvre, men in funny berets reading Sartre in cafes at dawn, and so on – but it’s not to be. Apparently there was some ‘football’ match there on Wednesday, the day of my arrival, between two teams called Arsehole and Bastard or something. Late on Wednesday night we were walking back to the lodgings and a crowd of Spanish ne’er-do-wells were destroying a street, uprooting small trees and heaving bricks through windows. And their team won, for God’s sake. Where were the famously brutal French police when they were needed?

I’ve nothing against peaceful people who love football, though I don’t care for it myself. But this sort of beast, apparently not just a British invention, should be flayed with a thorny scourge, then lowered into a vat of human excrement up to its chin, then made to bellow its monstrous chants at the top of its voice. Then thrown to the crocodiles.

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

Skinning up

I went for a walk in the woods a week or two ago as I was too tired to make my usual Friday evening excursion to the gym. It was a long walk, my three-year-old casual foot gear is past the point of being useful, and as a result I ended up with an enormous blister on my left big toe.

Last weekend I was watching David Cronenberg’s A History Of Violence with my customary bowl of peanuts at hand, and at some point I apparently peeled off my sock and picked at the aforementioned blister. Piercing blisters is generally recommended by medical science as it allows the serous fluid to escape before it turns into frank pus, and the layer of skin left behind provides an effective natural dressing for the tender sore beneath it. The problem arises when the blister has persisted after two weeks, post-piercing, and the skin has dried up over it. You tend to pick at the dead crisp epidermis without thinking, long after it has ceased to perform a useful function.

The upshot of all this is that at some point in my viewing of A History Of Violence, possibly during a fairly explicit sequence (which begins 16 minutes and 30 seconds from the start, not that I noticed it particularly), I must have contrived distractedly to place a fleck of toe-skin in my peanut bowl, because the thing I felt go down my gullet was sort of long and crisp and not at all like a nut.

So I suppose I am a foot eater after all! What are your favourite skin-eating experiences?

Last weekend I was watching David Cronenberg’s A History Of Violence with my customary bowl of peanuts at hand, and at some point I apparently peeled off my sock and picked at the aforementioned blister. Piercing blisters is generally recommended by medical science as it allows the serous fluid to escape before it turns into frank pus, and the layer of skin left behind provides an effective natural dressing for the tender sore beneath it. The problem arises when the blister has persisted after two weeks, post-piercing, and the skin has dried up over it. You tend to pick at the dead crisp epidermis without thinking, long after it has ceased to perform a useful function.

The upshot of all this is that at some point in my viewing of A History Of Violence, possibly during a fairly explicit sequence (which begins 16 minutes and 30 seconds from the start, not that I noticed it particularly), I must have contrived distractedly to place a fleck of toe-skin in my peanut bowl, because the thing I felt go down my gullet was sort of long and crisp and not at all like a nut.

So I suppose I am a foot eater after all! What are your favourite skin-eating experiences?

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Medical legends

A woman was admitted to hospital in a coma. She came round after eight months, and was found to be three months pregnant. A porter was arrested.

A hospital noticed an increase in patient mortality rates on Fridays. The phenomenon was investigated, and it was found that the cleaning lady, who vacuumed the wards every Friday, had been disconnecting life support systems in order to plug in the hoover.

A surgeon came out to the parking lot of his hospital to find his car broken into and the radio missing. Before he could report this, he was called urgently to theatre to treat a gunshot victim. It turned out that the patient had been shot by a security guard while trying to escape… after breaking into the surgeon’s car. The patient survived.

A patient was being given a rectal examination by a medical student, who rested his free hand on the patient’s shoulder. The consultant came into the cubicle to inspect the procedure, unbeknown to the patient, and rested his hand on the patient’s other shoulder. The patient fainted.

A surgeon was conducting his ward round when a nurse remarked that a particularly drunken patient was repeatedly pulling out his nasogastric tube. The surgeon asked the patient why he was doing this and the patient swore at him and pulled his tube out again. The surgeon drew a handgun from the pocket of his surgical scrubs and pointed it at the patient’s head. The man reinserted his nasogastric tube in record time and was as meek as a lamb for the rest of his admission.

A general practitioner was approached by a man who offered to clean his Porsche for five pounds. The doctor agreed, not knowing that the man was dissatisfied with the treatment he had given the man’s wife. When the GP came out to his car he found every inch of it cleaned – with a brick.

One of these stories I know to be completely true; one is partly true; one is possibly true; and the others are almost certainly fictional. I leave it up to you to decide which is which.

A hospital noticed an increase in patient mortality rates on Fridays. The phenomenon was investigated, and it was found that the cleaning lady, who vacuumed the wards every Friday, had been disconnecting life support systems in order to plug in the hoover.

A surgeon came out to the parking lot of his hospital to find his car broken into and the radio missing. Before he could report this, he was called urgently to theatre to treat a gunshot victim. It turned out that the patient had been shot by a security guard while trying to escape… after breaking into the surgeon’s car. The patient survived.

A patient was being given a rectal examination by a medical student, who rested his free hand on the patient’s shoulder. The consultant came into the cubicle to inspect the procedure, unbeknown to the patient, and rested his hand on the patient’s other shoulder. The patient fainted.

A surgeon was conducting his ward round when a nurse remarked that a particularly drunken patient was repeatedly pulling out his nasogastric tube. The surgeon asked the patient why he was doing this and the patient swore at him and pulled his tube out again. The surgeon drew a handgun from the pocket of his surgical scrubs and pointed it at the patient’s head. The man reinserted his nasogastric tube in record time and was as meek as a lamb for the rest of his admission.

A general practitioner was approached by a man who offered to clean his Porsche for five pounds. The doctor agreed, not knowing that the man was dissatisfied with the treatment he had given the man’s wife. When the GP came out to his car he found every inch of it cleaned – with a brick.

One of these stories I know to be completely true; one is partly true; one is possibly true; and the others are almost certainly fictional. I leave it up to you to decide which is which.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

The Depths

The next gust spills across the deck, the spray receding as the ship tilts, leaving foam scuds behind, and I watch them as they gnaw around my shoes. Through the brine and oil comes smoke, and I turn and find Kelly at my side. He always seems to be nearby, passing me in the corridor or appearing soundlessly when I am most alone, as now.

‘We lost a man last year, right where you’re standing.’

Kelly is short and squat and wind-blasted, his hair and beard an indistinguishable iron mass, yellow teeth clamped around his pipe. He leans on the rail beside me. The sea appears blackly alive, restless and constrained under the sky.

‘Name was Warner. Petty officer, four years on this bucket. I left him here one night, and no-one ever saw him again.’

I look at his eyes, for guilt or even unease, but the darkness hides him. I assume he wants me to show interest so I remain silent, trying to distinguish the seam of the horizon. I cannot, and it is suffocating, as though I am encased in the muffle of a wet cocoon.

Kelly nods over the side with his eyes and says, ‘They reckon the Kraken got him.’

The way he pronounces the two syllables suggests genuflexion and I am intrigued, and though I know what the word means I ask: ‘The Kraken.’

He raises his head, eyes half-closed. ‘A mile long, they say, living on the floor of the sea and surfacing when disturbed, not returning to its sleep until it’s taken something. Sometimes it’s a single man, sometimes a whole ship.’

‘So why did it come up this time? For this man Warner?’

He is still for a long time and then says, ‘He was married, had children. His wife said it was them or the sea. He chose the second, left them to themselves.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘He fought it. That was his mistake.’

‘I still don’t know what you mean.’

He turns his gaze on me and there is sadness and perhaps disappointment. ‘No. He probably slipped and fell overboard, anyway.’

I stare at him but he looks away again, and after a time I lean back and raise my face to the sky, where the blackness is almost blue and the stars are sprinkled like a city, blinking sometimes like beacons, or headlights…

I stumble away and as the heat and brightness of the cabin draws me in I feel Kelly and the sea watching me.

The day is there, grey and bleak, when I emerge. Again, the breach between sky and water is blurred, made more so by the skein of drizzle that never quite reaches the deck. I stand by the rail once more, declining the offer of a coat, wanting the chill to penetrate and numb me inside as well. In the light I see that the waves are not so much surging against the sky as pushing down, fighting to keep something buried. I sense a shifting far below, and as I peer into the white murk the ocean looks back at me, a giant speckled egg-pale eye bobbing. Fascination trumps horror and I stare as the eye rolls.

No, not an eye.

Mummy.

The word uncoils in me and grapples for my throat and instinctively I begin to collapse, but it is repeated, more insistently. A woman in a neon raincoat clutches at the hand of a boy, similarly hooded, as he stretches for the rail, face contorted with rage.

‘It’s gone, love,’ she coaxes. ‘We’ll get you another one.’

I cannot look at him and it would draw attention to appear aloof so I glance over the edge again, at the ball as it bumps and churns against the hull before being lost. Something tugs at my sleeve and I see with dread that the boy has broken free and is imploring me to rescue his toy. His mother catches up, flustered smile and shaking head, and seems to see something in my face which causes her to mutter a last apology before hustling the child away.

‘So what is it you do?’ Christiansen, the Chief Petty Officer, raises his eyebrows and probes around his squid, choosing a morsel of weed and mushrooms. I am at the captain’s table but the captain has been called away and I am making politely dull conversation with three other crew members. It is what I need, and I am relieved that the captain is absent, for his affability stirs feelings.

‘I sell books, up and down the country.’

‘You’re fairly quiet for a salesman. Makes a nice change.’ Seaweed, so green it is almost black, creeps from between his teeth. His tongue, pink and glistening, sucks it away. His coarseness, instead of being comforting in its superficiality, is threatening, and I feel the light of the dining room soften so that the other tables have faded and ours is illuminated in a finger of harsh light.

I smile, do not reply, and he fixes a sliver of squid with his fork and says, ‘Business good at the moment, then?’

He meant the holiday. ‘Not bad. I needed a bit of a break.’

‘Must be used to putting this stuff away, in your line of work.’ He pours whisky for himself and his fellow sailors, points the neck of the bottle at me. I am torn between the longing for oblivion and the horror of release of feeling and thought that will need to be endured on the way.

‘No thank you.’ My smile is thin.

He shrugs, unoffended. ‘Suppose you get used to not drinking, all that time you spend behind the wheel.’

The sudden wrenching scream of metal and rubber and the face, huge and white in the starry glass in the eternal instant before it spins away, the cold awful realization of a threshold crossed without the possibility of return…

I feel it rising within me, huge and powerful and apocalyptic, and I squeeze myself closed and focus on the wash of faces crowding over me, and dimly I am aware that it is subsiding, but it was close, perhaps closer than it has ever been.

‘I’m okay,’ I whisper when I can. ‘Just the squid, I think. Went down the wrong way.’ But Kelly, bristling and primal at the next table, is watching, and nods once to me, and I know that he sees as the others do not.

Oblivion’s pull dominates, as always, and I hook myself to the stool and swallow the liquid fire and watch the jerking of the bodies in the strobe-spasms. Some are vital, fuelled by hunger and lust and the need to connect; others move in slack parodies of human motion, as though the huge shifting mass of the ocean beneath us is making them sullen and desperate.

‘Same again.’

The small splash and trickle of the liquid into the glass is reassuring against the throb of the bass and the thin accompanying electronic sneer. I lift and swallow. Three more will be necessary; I have become an expert.

‘Not into it, then.’

Small and fair and dark-eyed, and I realize I have seen her before, caught a look of amusement across the dining room or on the deck or wherever. She leans her elbow on the bar counter and props her chin on the back of her hand. It is the last thing I want.

‘Sorry?’

‘All this.’ She waves a hand at the dance floor while looking at my face. Her makeup has been applied with exquisite care.

‘Not really.’ I raise my eyebrows at her glass and she pushes it forwards and I order for us both. I do not want this.

She has to lean her face in and raise her voice above the noise and I catch most of it: Julie or Judy, living in Hampshire, working in the clothing trade. I offer a few details, my gaze intermittent, hers steady. She tosses the pebble of her recent separation into my lap. I drink quickly, and feel the pull of recklessness.

‘It might never happen, you know.’

‘What?’ I stare at the gloss of her lips, wildly uncertain whether I have heard correctly. Her smile is closed and sad.

‘If you want to talk, you know, about anything, you can.’

The longing in me is a tightening truss that twists me in on myself and her eyes flicker at the pain she sees in my mouth and she places her hand on my knee. I hate the sea, hate Kelly and his sadism, and I reach for her.

Her eyes reach for me, then, and through their trembling film her sympathy dissolves into need and the engulfing horror of hope, and the surging of the pulse in my head becomes the rush of wind through shattered glass and I fall away towards the doors. Behind, through the shriek of brakes, the sobs chase me, and below, the rumble of unslaked hunger rises like a laugh.

The towel folded over the rail in the bathroom has a yellow-on-blue motif which at first I take to be a portrayal of a starfish; closer inspection reveals nine tentacles, an enormous disc of an eye, a beaked maw. I prop myself against the headboard of the bed and watch television. A gateway to another dimension extrudes a serpent, then its mate, then another and another, identical fleshy headless parts of the same whole, lined with suckers. I switch off and lie still, and clothes hanging on the closet door merge, jacket and trousers becoming each other, arms and legs moving sinuously. I close my eyes and the pulse behind the lids spreads into the mesh of capillaries, invading my darkness.

I am standing on a raft, uneven logs lashed together crudely. All around is chaos, the sea screaming in pain and delight, rain stabbing mercilessly at the surface. Through the blackness I see the ship ahead of me, abandoning me. I reach out for it, as far as I can without toppling over the edge, and a figure standing at the rail, indistinguishable with the eyes, calls out to me: Kelly, his voice impossibly clear.

Let it come.

Face it.

The raft tilts backwards and I brace my legs, but it does not right itself. With dread I take my eyes off the receding ship and turn. Across the far end of the raft lies an enormous appendage, thick at its base and dwindling to a fleshy point, twitching, glistening. I squat, as if I can make myself heavier by concentrating my mass, and as I do so another tentacle smacks across the raft, joining its twin from the opposite side. The wooden frame groans upwards, tipping to a point where I feel myself sliding, and I grasp the rough splintery edge with one hand, flailing with the other in a primitive warding-off gesture. The raft stands almost vertical now, and I drag myself to the summit and stare down at the sea, alive with writhing sensuous movement which, horribly, comes from the same stem. The ship is a toy on the horizon now, but even so I catch myself judging distances, the time it would take to spring off the disappearing platform and strike out for the dwindling haven of solidity and familiarity.

And then I know it is too late as the first flicker of oily tongue finds my foot, tastes and then clamps, and another seizes me higher up around the bulk of the thigh. My shrieks are pathetic and the shame eats at me as the gnawing hunger below me suckles and with a cry of desolation I surrender myself to the thing beneath the waves.

At first I feel I am clinging to a rope from the ship’s hull until, a few heartbeats later, I realize I am gripping the wadded-up sheet in my fists and the cold and damp is my own sweat. I am unsure whether I screamed, and listen for hurried footsteps, but the gentle lap and creak of the ship in harmony with the sea is undisturbed.

When I can breathe again I sit up in the black and peer through the porthole’s curtains. The closeness of the water is disturbing, and I recoil as a wave uncurls itself and slaps the glass. At this distance I can see my reflection, as though lost in the ocean and begging for entry, but it is indistinct, and could belong to anybody, someone younger, a child…

I know now what I must do, and with this knowledge comes urgency, a panicky desire for release. I scramble into my clothes and make my way through the darkness of the corridor and up the stairs to the deck. The night is surprisingly still, with a cold beauty. He is there, of course, and I do not look directly at him but go to my spot at the rail, afraid to the point where I cannot feel it any longer, and breathe in the salt and sealife, and close my eyes in calm.

The boy comes running out of the shadows, a blur of red and white, his tiny face growing vast and splitting into an O of horror as the howl of the brakes mocks him, laughs at me, through the shattering sideways spin of the car after it is too late for either of us, two lives meeting and ending as suddenly. The scene has played itself a thousand times before, and I have watched it with disinterest, as I related it in the court, staring at the coldness in the four men and the eight women sitting in judgment over me, at the moues and averted gazes of revulsion, and worse, the sallow red-rimmed mother’s face behind me burning into my back. I have thought that by watching it over and over I will break its hold on me, but now I realise I have never really watched it at all, not in any real sense.

I start at the beginning, then, with the soft whirr of the tyres on the silent road, and I hold the image until I can hear it, can smell the sodden birch leaves and diesel and savour the tang of the pollen on my tongue and palate and the tickle of exhilaration of rapid motion and a future of unbridled delight. My breathing and my heart quicken, and I stay aware of this, as though it is happening in the relived scene. The hill is ahead of me and I climb it, gearing down, whistling to the tune on the radio as I reach the crest and edge the accelerator down, the road diving into the trees and vivid in the dusk and welcoming before me. The freedom of the road, the sexual promise of speed and vitality and naked nymphs baring themselves to me from the engulfing forest and later in sweaty cheap traffic-circle hotels, and oh God, life is wonderful…

The first flash of the boy appears from the trees to the right…

And I open my eyes and stare down at the brooding sea and summon the Kraken from the depths.

Confessional again

I’ve run out of ideas for posts. Been there, done that, I think whenever a promising notion drifts into my head. In truth, lately I’m rather enjoying keeping a low profile, reading everyone else’s blogs and occasionally commenting. Hiding has its pleasures. As time goes on, I’ll post more. I’ve a backlog of unpublished short stories, some of which I’m thinking of posting here, though they’re not always exactly in humorous vein. Got to polish them up first, though, for such a discerning readership. In case they prove too big or nobody ends up reading them, I need to figure out a way to store them somewhere else and link to them from this blog. Trouble is, I don’t have the technical know-how. For instance, I know Blogger allows you to have a blog within a blog, but I haven’t worked out what this means yet. Blogging was never meant for idiots like me. At least, that’s what the man at the Blogger help desk says. Work out what I’m really saying with this post, if you’re curious.

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

Public service announcement

I just thought I'd let everybody know that I haven't been posting much lately.