Saturday, May 27, 2006

The Woodborn (part one)

He had opened the first box and was lifting Tomas out, taking care not to entangle the limbs in the strings, when he saw the little girl approaching through the pale sunlit dust. He stopped and watched as she strode towards him, wearing the shabby blue dress, the solemn pinched expression, the staff of bare smooth wood hanging from her fist. She stopped before him, staring at Tomas, and he smiled.

‘Good morning.’

He lifted the wooden cross above Tomas so that the puppet sprang to life, and tilted his wrist so that it raised its arm in greeting. ‘Tomas says hello.’

She raised a small fist in response. Tomas was clad in a gaudy billowing blouse and trousers with white and scarlet stripes, and he placed his hands behind his enormous ears and grinned at her, bending his knees and kicking his pointed green shoes up in turn. The puncture of her mouth grew into a line, and she clapped her hands and her eyes widened at the old man. He felt the pain of dawn on frosted glass.

Still working Tomas with his right hand, he reached across and tipped the lid off the second box with his left and reached in and brought out Frieda. Her bulb cheeks and sausage nose could make her Tomas’s sister or mother or daughter; often she was his wife or sweetheart. Today he had dressed her in a yellow satin tunic and a skirt like a bell, that would flare as she twirled. He had hoped the little girl would come.

There was a wooden stool that he kept varnished, but the little girl never sat. She stood with her feet together, hands clasped, serious again. He began the tale, shortening and simplifying it, hiding each character in turn behind a box while the other took the centre. He told of Frieda, the little girl who lived with her woodcutter father and drew water every morning from the stream in the woods, content to help her father but without joy in her life; of Tomas, the boy with music in his heart but also loneliness; of Tomas’s long hours staring at himself in the surface of the stream in the woods, wishing for a different face to look back at him, until he lost his balance and fell into the water and was washed for miles until Frieda pulled him out. The old man chose high sad tones for Frieda, deepened his natural voice into a duck-like jabber for Tomas which had the little girl shrieking with glee. When he tumbled Tomas into a chaos of flailing limbs for the drowning scene, his tone rose until he realised he was shouting and the girl looked so frightened he thought she would wail; the rescue was done so deftly, the girl-puppet rushing out from behind the box and drawing attention away from his right hand which gripped Tomas’s strings and jerked him to a stop, that the little girl gasped.

He made Tomas’s splutters and panting die slowly, and paused deliberately, enjoying the annoyance this always provoked in his audience, the impatience for resolution. The little girl had not seen this tale before, and she stared from puppet to puppet to their master, her eyes begging him not to let it be finished.

‘Do you know what they did then?’ he asked gently. She shook her head, breathing through her mouth as if trying to keep silent. He leaned forward, laughing inside as she did the same, craning her eyes and ears towards the secret.

‘They danced.’

A faint line separated her brows as she moved her lips around the taste of the word, and he felt the sting in his eyes and his throat and thought: she doesn’t know it. He whispered to the question in her gaze, ‘This,’ and it began in his head with a great organ flourish, it was always an organ, no matter what the tune, and the chords were major, starting slowly and softly and made physical in the turning of the two puppets to face one another and the shy reaching of their arms for each other, and building so that he closed his eyes and summoned the orchestra from far within him and unleashed it through the arms and legs of string and wood and cloth until he could hear the little girl far below him screaming and stamping in delight and could see through his closed lids the whirling marionettes, young and alive and dying.

The ride had not been a good one. Twice the driver had had to brake and swerve, the first time to avoid a pothole that would have certainly damaged the car’s axle, the second to swing clear of a dark shape in the centre of the road over which a sack had been carelessly flung. The second time the driver had not been so quick, and the left front wheel had rocked over the corpse’s head and burst it.

Kessler stepped from the car and watched the black uniforms slot themselves rapidly into a single row, nineteen in all. The lieutenant strode towards him and snapped a salute.

‘Colonel. Eternal glory to the Renewal.’

‘Secured?’

‘Yes, sir. The entire area.’

He walked down the line, not looking at the men, feeling them stiffen as he passed each one. Beyond them, mounds of smoke fumbled across the wreckage of rooftops, dragged behind a tired wind. By the side of the road, in a gravel half-moon in front of an inn of some kind, about thirty people lay face down in silence, hands clasped behind their heads, soldiers standing over them. He stopped and jerked his head. The soldiers shouted and jabbed with their rifles and the people began to pull themselves to their feet. A low whisper started and there was brushing of dust off clothes and the soldiers yelled again and the hands went behind the heads.

Kessler examined the group. Perhaps a third were women. The faces were pale and sullen, glowering through streaky dirt. Most were young, in their twenties or thirties, though there were three or four grey heads. It was one of these that he needed.

He selected a man standing close to a younger woman, and muttered to the lieutenant. A soldier moved and the man stepped forward and apart, the woman making a soft cry and her hands moving to her mouth, and he knew he had chosen well.

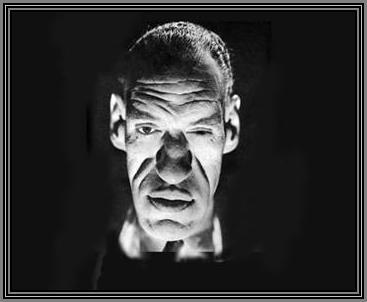

In the inn, the man sat, his rough veined hands clasped before him and the hate-lust in his shadowed eyes. Kessler stood over him and gazed at the ceiling with its black stoic beams. He watched the beams for a long time, and then dropped his eyes, not to the man but to the soldier to his right, crisp and pink-shaven, and said, ‘Where is the base.’

There was silence, and from the man on the rim of his vision, not feigned incomprehension, not outrage, but hate, simple and honest and direct. It was not enough.

A nod to the lieutenant at the door and the door opened and through the stillness, there were shouts and a crash and then the punctuation of silence. The door slammed open and the body was flung with a wet smack to sprawl twist-necked on the floor to the man’s left.

Kessler watched the face. He spoke rapidly, with the detachment of authority. The lieutenant had briefed him quickly, and he had listened.

‘This is your eldest daughter, Sara. You have a son, Jonah, aged thirteen, and a daughter, Faye, seven. Where is the base.’

The eyes were seeking his now, yellow, even the irises, and the hate was there but small, like a child’s fist, and within the huge darkness of the pupils he saw the man, bent and crawling in a void with his light shattered and gone and his, Kessler’s, face luminous and swelling before him.

He had chosen well.

The base was twenty kilometres away, in a dismal country slope of firs and logs and a river, secret but indefensible, pathetic. Ground troops, then, half a day and it would be over, wiped like a smudge from a glass. He watched the man while the lieutenant made notes and spoke sharp quick orders into his hand. The man did not look at the body, his blue-cabled hands still, the flesh of his face wondering vaguely why it lagged behind him in the death journey. Kessler stepped forward and pushed the end of a cigarette between the man’s lips and lit it, and still the hands did not move, the slow intake and exhalation of breath dragging out the gnarl of ash. Kessler clipped open the holster at his belt and drew his pistol and shot the man in the head, and the hand on the floor hurled wide from the body twitched at him before curling.

They had come to the old man one evening after the sun had dragged the thin autumn light beyond the pines, tapping on the door of his hut, and he had opened the door as he would have if they had hammered with their fists. Four of them, each young, each with the grim heroic certainty in his brow, and the fear apparent in a shift of the eyes or a too-frequent settling of weight from one foot to the other.

‘You do not realise the influence you have.’

‘You can keep the spirit of the Resistance alive here.’

‘You have an obligation to the children, to all of us. You do not exist alone.’

They had spoken of subtlety, of a message so ghost-like it would be like the pulse of blood in the viewers’ veins, unconscious yet vital. One of them had pulled a grubby sheaf from his pocket and thrust it at him with the awkwardness of the shy. It had been a script, written as dialogue in the manner of a play, full of parenthetical grimaces and sneers for the actors, and concerning the exploits of Dick and Tor and their building of a ship using the slave-labour of the village which they ruled, the sabotage of the ship by the villagers and its sinking. Dick and Tor’s ship. Dictatorship. It had been years since he had wept, but he had wanted to weep as he handed the sheaf back to the young man.

To their hurt angry stares, as he had closed the door, he had said simply, ‘I make my puppets dance. That’s all they need to see,’ and he had watched them through the crack of night and forest, looking for a blink of understanding, seeing nothing but despair and bewilderment. He had gone to the back of the tiny hut and opened the boxes and Tomas and Frieda had clambered to life, grinning their wooden innocence at him, and as they had started a gentle waltz he saw behind his eyes Tomas in mud-smeared victory holding aloft a bloody bayonet, and Frieda marching up a staircase of skulls with the troop of children behind her, the little girl at the head, and he knew that he would rather cut the life from their strings and see them sagged and silent.

Twenty years ago he had come to the village, and the stories he had told with his wrists and his fingers had altered little, as the children had grown and drifted away and a new generation had come to him. He had watched them, sifting through the reactions in the tiny faces, making Tomas and Frieda respond until the cells of the audience had over weeks, months, knitted together into a breathing tissue. Then five years ago, the change had come in a chill raw wind that had crawled across the land through the village, so that the new group of children had come to him blank and stunted, the words from their mouths no longer wondrous and new but withered and as coarse and unquestioned as the dissolving of the old hard bread in their bellies. He had sat alone by the guttering table-lamp, his new duty a majestic horse-backed pioneer in his thoughts, a tight mocking horror in his stomach. In the years since, he had listened to the whispers creeping from the trees, the hissed rage at the apathy and fear of the village which had become a snarl that retched out crude pamphlets in the streets shrieking warnings about the slaughter of collaborators. He had sat in the desolation of aloneness and had come to welcome it, for it allowed him nowhere to turn for distraction, forced his focus on Tomas and Frieda and his audience, and he had played and danced the puppets and for a few hours each day, he felt drunk on the simple cleanness of truth.

Comments:

<< Home

Right now, (pauses, takes big drag on Capstan Full Strength, goes to roll up sleeves again) what's all this about Mr Eater?

I've read it twice now and I'll be honest with you; I don't think it's suitable for the school library.

The puppets alone.

I'll read the next bit when you're ready.

I've read it twice now and I'll be honest with you; I don't think it's suitable for the school library.

The puppets alone.

I'll read the next bit when you're ready.

Thanks, Sarah, and Doc (I think). I doubt many people will read this, but if you do, please stick with it. It's an old story I wrote years ago which I've chopped up into three parts. The prose is far too overwrought and liturgical for my tastes nowadays, but I still like the idea; and the ending, if you get that far, is quite clever, I think.

I've read it, and I really enjoyed it.

I loved each of the disparate parts, each had a good distinct flavor.

Is there more to come? I would very much like to know the where and the when of this tale.

I loved each of the disparate parts, each had a good distinct flavor.

Is there more to come? I would very much like to know the where and the when of this tale.

I'll read the next bit when you're ready also, Mr. Footsie, though it gave me a slight touch of the horrors. I may need a Valium tonight.

Post a Comment

<< Home