Monday, January 16, 2012

Cliffs

Tradition based on common sense dictated that we do it at dawn: the likelihood of discovery by a passerby was small, and although the middle of the night would have been even better in this regard, it would have been foolhardy to attempt the climb in the dark. Thurston and Field, the two boarders, had appeared over the wall where Quinlan and I were waiting and we made our way at a pace over the main road and along the rough path that had been trodden into the field rising eastwards beyond which gulls called and wheeled. We fell into spontaneous formation as we strode, Quinlan in front, the boarders trailing them and I some distance behind.

Half an hour’s walk led us to the cliff’s edge and we followed it northwards as to our right the sun broke over the skyline and bled across the sea. Leaving behind us and inland the tiny church with its graveyard, where so many former pupils and masters of the school had come to rest, we began a steeper climb than before, having here and there to clamber over boulders using our hands. Ahead I watched Quinlan haul himself over the side of a flat-topped rock and disappear. Thurston was next. Field, mildly overweight and sweating in the pullover he was wearing against the early morning May chill, struggled, his legs failing to afford him the necessary momentum.

‘Do you want a hand?’ I said.

He frowned down past me, then lunged once more and this time cleared the edge of the boulder.

The surface of the rock was flat and broad with plenty of room to walk about or even lie down, which Thurston did, making a show of basking in the sun. Quinlan shuffled forwards with mincing steps until his toes were inches from the lip of the rock. He peered down, then reeled away: ‘Whoah, God,’ his laugh flippant and tinted with genuine panic. The rest of us followed his example – we had to – and when Field turned from the edge his cough made me wonder if he were going to be sick.

It was a drop of a hundred feet, a pitted wall of limestone sweeping down to a rind of ragged boulders interspersed with shingle, not entirely perpendicular but sheer enough that if you were to take a running jump you could spring out far enough to plummet directly on to the ground below. The beach was closed off on its northern aspect by the curve of the cliff, and to the south a path sloped upwards narrowly for several hundred feet to join the cliff path along which we had come. That was the exit we would take from the beach, afterwards.

We stood in a loose circle, unsure what to do next and assuming Quinlan, the unspoken leader of our group by virtue of his height and the size of his personality, would guide us. He grinned, smirked almost, aware himself of how the power relationship had come suddenly into focus. With his fingers he motioned us to stand side by side with our backs to the north-stretching cliff edge which formed an immediately recognisable vista. Facing us, he extended his arm with his mobile phone in his hand and snapped us.

There was always a photograph, there had been one every year for decades, even in the days before mobiles and digital cameras. The reason was one of incentive: a boy was less likely to back out, to bottle it, once there was photographic proof of his having been on the scene. Quinlan peered at the phone to check the quality of the picture, then frowned.

‘What?’ said Thurston. He worshipped Quinlan and displayed his sycophancy in a surly, nonchalant way, his neediness all the more visible for it. Quinlan shook his head.

‘Thought I saw something in the picture, that’s all.’ Then, brightly: ‘Hey, probably Cliff.’

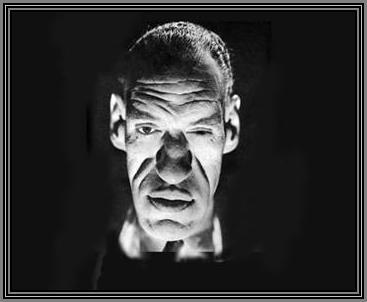

Cliff was the boy who had fallen to his death during the climb, as legend had it, the only boy to do so in over ninety years of the ritual. Nobody knew quite when he’d done so, common consent having it that it was during the nineteen thirties or ’forties. Nobody knew, either, whether he had been buried in the graveyard of the church we’d passed, nor even what he had really been called, “Cliff” representing a stab at a witty nickname. Over the years several boys had claimed to have felt Cliff’s presence or even seen him during the climb, peering over the edge above them as they descended or clinging to a promontory as they passed it.

The rules were simple. Each year, any boy was free to volunteer for the climb. Most were twelve years old. There was no shame in not volunteering – in some years as few as two boys undertook the descent – but there was considerable prestige in completing it. In order to keep the adults, the masters and the parents, in the dark about the ritual, nothing was written down, no records were kept; but you passed into legend if you did it, survived the throttling terror of the sheer descent with Cliff near by all the while. Shame, profound and never to be expunged, came from backing down once on the cliff. Once, in the history of the school, a boy had backed down.

Quinlan put away his phone and stepped to the edge once more, the decision having been taken wordlessly: he would go first. His face was unreadable, braced, as he lowered himself so that he was sitting with his legs hanging over the edge. Thurston advanced, frowning, not blinking, gaze fixed on Quinlan. Behind me, Field muttered: ‘Teacher’. I turned, expecting Mr Halliday to have appeared on the rock, boy-hating muscles bracketing his eyes and mouth, but there was no-one. Field gave what he probably intended as a wry chuckle but which emerged as a giggle, high and nervous.

In an instant Quinlan was up off the edge and rushing Field and with a punch in the chest he sent him sprawling. Thurston grinned, slapped him on the shoulder. Quinlan shrugged his hand away and turned back to the edge and said, ‘You go after me, Simon’. I glanced at his face but he meant the other Simon, Thurston. Field was picking himself up and dusting himself, face burning.

We joined Quinlan at the edge as he swung himself over, torso pressed against the cliff face and hands gripping the lip of the rock. The rapidly climbing sun was washing the beach clean of shadow below. There was little wind and the tide was sluggish, the low waves flopping on the shore and wheezing back through the shingle. The beach, the rocks immediately below us, were impossibly far, and staring down at them made them appear to wheel. Quinlan began to descend.

Near the top the hand- and footholds were abundant; about halfway down the cragginess began to yield to sheer expanses of rock. Terrifying though the first gropings were, it was at these smooth sheets that boys in years before reported they had first begun to panic – at least, those who were willing to admit they’d been frightened. Quinlan hadn’t reached this point, was twenty feet or so down, when his head whipped back so that he was staring at our faces where we crouched or lay peering over the edge at him. His eyes were dark pits of fear.

‘It’s so cold… can you feel it?’ he called. Then: ‘There’s something here. Something on the cliff with me.’

Beside me I noticed Field had gripped Thurston’s upper arm. Thurston flung the hand away.

Quinlan’s voice rose to a high keening. ‘Oh God – there’s something here.’

He screamed then, except it was too nearby to come from him; Field and Thurston had both given voice. Below us Quinlan’s right hand jerked free from the cliff face, the piece of rock he had been gripping spinning away and down and leaping off the rocks below with the tiniest crack. His clawed hand flailed and scrabbled at the face and the toes of one of his trainers rasped loose from their hole so that he was clinging two-limbed to the wall.

I broke away and wandered along the flat rock, hearing behind me Field and Thurston gasp and mutter and finally laugh, and from below came a shout of triumph. When I returned and looked down Quinlan was clambering at great speed down the face, weaving and skittering like an arachnid, until with a whoop he leaped the last few metres and rolled and stood on the shingle with his fists raised to the sun.

Fifty minutes later, Field having taken longest but having received enthusiastic support from Quinlan and Thurston on the beach, magnanimous in their shared glory, I began my own climb; and I shimmered down expertly, gracefully even, using the jags and outcroppings and occasional stumps of tree branches as a gymnast uses the bars, exulting in the supple flow of my limbs and the growing heat of the sun against my back. Once I looked up, imagining Mr Halliday to be peering down, but the skyline was empty. I’d set my watch and I completed the climb in a time that was a record for me and possibly one for all time. The final thrilling three-metre drop brought me on to the shingle and I straightened and turned to find the other three boys.

But they were gone, a three-headed creature disappearing into the distance far along the path that led up and away from the beach, their excited voices drifting back now and then.

*

I walked back to the tiny church and strolled amongst the gravestones. Church and graveyard had predated the establishment of the school by three centuries, but for the last hundred years the school had owned them. I stopped at one headstone and read the inscription:

George Henry Halliday, 1894-1960

Beloved Master, Husband and Father

My own bones weren’t here in the school graveyard. They were coffined on another continent in a spot marking a full stop to a life, bracketed by the dates 1923 and 2007, that had been to all appearances modestly successful but which I had endured as one of deep, pervasive failure, of abiding shame. Once dead we realise what matters in life, how the past chains us, and the discovery is horrifying.

I hadn’t meant to make him fall, Quinlan, and I was glad he hadn’t. I’d wanted to scare him off the climb, and I’d chosen him out of anger because he’d been so beastly – such an old-fashioned word now, yet so apt! – to Field, making him go last. Being the last to climb was the worst because you had nobody above you to look up to for support and encouragement. I knew now I shouldn’t have chosen Quinlan. He was too strong; I should have waited and picked on poor friendless Field, made him conscious of my presence and scared him off the cliff, turned him into a failure like me.

Until next year then, I thought, and I stood and walked away from the grave of Mr Halliday and possibly the grave of the legendary Cliff and the future graves of Quinlan and Thurston and Field and countless others, who despite their animosities and even mutual hatreds in some cases were united by the fact that here, in the churchyard and the school and on the cliff, they had a place where they truly belonged.