Saturday, June 03, 2006

The Woodborn (part three)

‘It is in the wrists, and in the fingers.’

It was Kessler’s fourth day, his eighth lesson.

‘In the fingers, especially. The wrists are the leaps, the dips. The fingers are the pivots and the dancing.’

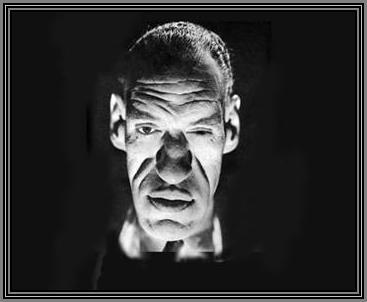

The old man lied to him. The wrists were the force of the hammer-blow to the nose, minimum energy channelled into the maximum pain, the fragmenting of bone and shearing of tissue, effortlessly shattering the integrity of the physical self, the discrepancy shocking and therefore undermining the more fundamental sense of wholeness. The wrists were the twisting of the ear, of the sex, the head on its axis. The fingers were the pressing of air from the trachea, the damming of the lifeblood in the thick vessels of the throat, the slow drawing back of the trigger into the release of noise and fire. Wrists, fingers, they were tools, not secrets, and utterly without meaning. He stood, uniformed in black and gold, beneath the reach of the branches, the twin bundles of wood and string twitching stupidly from his splayed hands and the ravaged ancient close against his back, the knotted claws gripping his forearms and the dry rotting-wood breath at his cheek, and the urge rushed from his belly like gorge: the urge to use the tools, to smash the old man and the ridiculous old puppets into splinters and to crumble the splinters into ash, then to bathe the village and its forest-father in a sea of fire. He cast his eyes up, imagining the branches drowned in flame, black char toppling and dissolving, the secret gone in the final laughter of the wind.

The elder released his arms as if sensing a change in him and he turned, gently, and the puppets were cast aside with a soft dry sound behind him and he took hold of the hard bulbs of the shoulders through their sack-wrapping and his face was close to the other’s; he could not see, through the hazy veils of the eyes, the shadows behind, but he knew from the stillness of the distorted old frame that he was seen, and was understood.

‘Do you see?’ he whispered. His arms shook the frail body. ‘Do you see what I must have?’

The voice was as low as a wind trapped for aeons in the forest: ‘Yes.’

He released, stepped away, not afraid. He stood erect, his hands by his sides.

‘Show me now.’

Within an hour, the old man had reached the tree. The moon, its sheet dispersed through the sieve of the leaves and branches into a silver rain, had at first allowed him to step over the exposed roots and moss-hugged fallen trunks, to prise his way between the snarl of arms and vines. As he had sunk deeper, the rawness had engulfed him so that the light had retreated, beaten, and once the false guide of a forest-creature’s eyes, flat green winking discs directly before him, had tricked him over the bank of a small gully so that he had sprawled with a gasp, and lain with his mouth pressed into trickling sweet earth, the rushing in his brow seeking the rhythms of the enclosing dark.

He stood before the tree, its brawny torso splashed with a torrent of white from a space in the canopy far above. The tree was father and mother, its great branches fisting upwards from the puckered wrinkles of the birth-scars near its base. The older and lower wounds, the places from which he had hacked the branches from which he had carved Tomas, were furred with moss; the newer Frieda-cuts were still angry and blistered with dried sap. Twenty years ago, he had been midwife to Tomas; ten years later he had brought him a mate; and the parent was slow to forget.

He knelt before the mighty base, for the tree was to him as fifty generations were to the innocents who clustered about him daily in mute reverence. He knelt, the pain of the hard damp knots of stone and root pinching his bony knees, and above the soft murmur of the forest’s wind and the teeming night noises of its offspring, he began his confession.

I have given you to another.

I have taken what you have given and I have soiled it, spat on it.

He did not say, I have protected your children, for he had taken those children by force. He did not bury his face into the forest floor, rage into the night, beg the parent to maim him, twist the life from him. Excuse, self-abasement, had no place in the presence of the dreadful wisdom of the parent.

By unspoken command his head was raised and, neck craned, he gazed at the bole above, its coat of cold pale fire-light glimmering. The parent stared down at him, at the being at its foot who had stabbed and rent it, ripping the two tiny doll-bodies from its flesh, and he thought it no more felt the absence of its spawn than the ocean resented a child’s scoop from its rim. The removal had extended its grasp, no more; had spread the reach of its power. And he knew then that the power remained that of the parent, could not be transferred, and that he had given nothing to the man.

This time, as he made his way back, the light remained, his footfalls true and effortless; and once, when he paused to slow his breath, he felt the glitter of tears on his face.

Noon, and the sun was his spotlight, its bright stare proper for the occasion, yesterday’s milk-filter gone. Kessler’s tunic shone blackly, the sleeves rolled up. His wife had shone the buttons well: a favourite dress, a smile of affection, would be her rewards, were owed to her.

The tableau was imbalanced: before him, the perfect chaotic spontaneity of the children, thirty again, in their half-circle, the force of their expressions combining a few feet ahead of them and channelled at him, no surprise in the solemn faces, no wonder at the unfamiliar scene. But to his left, wavering at the interface between illusion and invisibility, the brittle figure, hands clasped in front of its scrawny sack-clad belly, and he fancied its eyes were on the crates at his feet.

In the bright silence, he reached into the box at his right hand and clasped the jointed cross and lifted the girl-puppet into the light. He had mastered the technique of watching the puppet with one eye, his other on his audience, and he was looking for a ripple of surprise. He was disappointed to see none. Perhaps the old man himself had sometimes begun stories with the girl-puppet rather than her mate. His fingers felt more natural, more at ease, manipulating this one.

‘Here I am, all alone, with nobody to play with.’

He felt a flicker of satisfaction as he heard his voice, normally a carefully modulated tenor, now raised perfectly into a little girl’s plaintive murmur. His technique was expert, the wooden hands deftly manoeuvred so that they appeared to be clasped before her in dejection. He breathed, as the old man had taught him to breathe, drawing the vastness of the forest behind into his chest. His scorn and disbelief, which had at first threatened to deafen and blind him to the elder’s instruction, he had learned to suspend: strategy was all, for now, until he had made the power his, and then the pathetic superstitions would be tossed aside, broken and dead.

It was not until the boy-puppet, Tomas (as he was now called; the names would need to be changed) stood and jigged beside its companion that he became aware of how completely he had given himself to the ‘strategy’, for he realised that he had not been watching his audience with one eye, had not, in fact, been conscious of seeing anything at all. He spoke and his fingers and his wrists played, and he saw that the children’s gazes were on the puppets. He scanned the faces quickly, the shadow of an impression flitting almost beyond the reach of his awareness until he grasped and identified it. The children’s eyes were not moving to follow the bobbings and weavings of the wooden figures; seemed, in fact, to be focused beyond the puppets, beyond him.

He was gripped by an urge to look behind him at the forest and he resisted, staring instead at the dancing figures. Their motion drew his gaze, distorted the perspective so that the puppets appeared taller, their heads now at the level of his waist. Then he realised his hands had stopped moving.

From behind there was an awful pressure on his back, and he felt himself impelled forward towards the skipping marionettes. He could focus on them now without lowering his gaze from the horizontal, and as the round wooden skulls swivelled and the painted grins faced him, he saw the children, risen to their feet and grown huge, approach.

His hands flailed at the sky, his feet jerking and scrabbling in the dust until he was grasping nothing yet was somehow lifted from the dirt floor, his head bobbing so that his vision trembled. He opened his mouth to shout, found his lips clamped shut and curved downwards obscenely at the corners, a parody of tragedy between the dual gaieties of Frieda and Tomas. He tried to blink, could not: a not-face to accompany his not-limbs. He wanted to look above him and, when he felt a tug, let his head loll back.

From his hands, from his head, strings converged in a foreshortened steeple to a wooden cross around the centre of which curled the gnarled knuckles of an enormous hand. The cross and the hand obscured most of the old man’s face, one yellow eye visible peering down across the wildness of his beard. A twitch of the hand and he felt his head bounce forward again. Knees and skirts and ragged small shoes hovered before his gaze, and were replaced gradually by giant faces as the children crouched to look at him. He found it difficult to focus on any single point, his movements were becoming more rapid, more complex, but nevertheless he picked out one face: it was a little girl, her tiny mouth and huge eyes solemn, a staff of wood grasped in both hands across her lap.

He could not blink, he could not move his limbs, he could no longer even feel the movements at his joints, his awareness shrunk to the field of vision directly ahead of him and to a vague sense of self within the confines of his tiny head; a self so purely passive he marvelled at it. He had known passionately all his life that this state was achievable, had held on to this belief in the face of defiance and ridicule; how delightful, how ironic, that he, who had striven to cultivate it in others, had now attained it himself!

He found himself facing the girl-puppet, Frieda, and the way they whirled and dipped in tandem made him realise he was dancing with her. Her face, so crass and gaudy before, was beautiful, he saw now that he was close. They were spinning so fast that the wood was no longer behind but formed the walls of a tunnel around them, and he was dimly aware that others had drawn near, the adult villagers and even, he fancied for an instant, his wife, his son. The old man, the children, the forest, were his masters, immense and absolute, best ignored: for here was Frieda, and Tomas who had joined the dance and smiled and nodded at him, and here, among his new companions, he felt at last that he truly belonged.

Finis

It was Kessler’s fourth day, his eighth lesson.

‘In the fingers, especially. The wrists are the leaps, the dips. The fingers are the pivots and the dancing.’

The old man lied to him. The wrists were the force of the hammer-blow to the nose, minimum energy channelled into the maximum pain, the fragmenting of bone and shearing of tissue, effortlessly shattering the integrity of the physical self, the discrepancy shocking and therefore undermining the more fundamental sense of wholeness. The wrists were the twisting of the ear, of the sex, the head on its axis. The fingers were the pressing of air from the trachea, the damming of the lifeblood in the thick vessels of the throat, the slow drawing back of the trigger into the release of noise and fire. Wrists, fingers, they were tools, not secrets, and utterly without meaning. He stood, uniformed in black and gold, beneath the reach of the branches, the twin bundles of wood and string twitching stupidly from his splayed hands and the ravaged ancient close against his back, the knotted claws gripping his forearms and the dry rotting-wood breath at his cheek, and the urge rushed from his belly like gorge: the urge to use the tools, to smash the old man and the ridiculous old puppets into splinters and to crumble the splinters into ash, then to bathe the village and its forest-father in a sea of fire. He cast his eyes up, imagining the branches drowned in flame, black char toppling and dissolving, the secret gone in the final laughter of the wind.

The elder released his arms as if sensing a change in him and he turned, gently, and the puppets were cast aside with a soft dry sound behind him and he took hold of the hard bulbs of the shoulders through their sack-wrapping and his face was close to the other’s; he could not see, through the hazy veils of the eyes, the shadows behind, but he knew from the stillness of the distorted old frame that he was seen, and was understood.

‘Do you see?’ he whispered. His arms shook the frail body. ‘Do you see what I must have?’

The voice was as low as a wind trapped for aeons in the forest: ‘Yes.’

He released, stepped away, not afraid. He stood erect, his hands by his sides.

‘Show me now.’

Within an hour, the old man had reached the tree. The moon, its sheet dispersed through the sieve of the leaves and branches into a silver rain, had at first allowed him to step over the exposed roots and moss-hugged fallen trunks, to prise his way between the snarl of arms and vines. As he had sunk deeper, the rawness had engulfed him so that the light had retreated, beaten, and once the false guide of a forest-creature’s eyes, flat green winking discs directly before him, had tricked him over the bank of a small gully so that he had sprawled with a gasp, and lain with his mouth pressed into trickling sweet earth, the rushing in his brow seeking the rhythms of the enclosing dark.

He stood before the tree, its brawny torso splashed with a torrent of white from a space in the canopy far above. The tree was father and mother, its great branches fisting upwards from the puckered wrinkles of the birth-scars near its base. The older and lower wounds, the places from which he had hacked the branches from which he had carved Tomas, were furred with moss; the newer Frieda-cuts were still angry and blistered with dried sap. Twenty years ago, he had been midwife to Tomas; ten years later he had brought him a mate; and the parent was slow to forget.

He knelt before the mighty base, for the tree was to him as fifty generations were to the innocents who clustered about him daily in mute reverence. He knelt, the pain of the hard damp knots of stone and root pinching his bony knees, and above the soft murmur of the forest’s wind and the teeming night noises of its offspring, he began his confession.

I have given you to another.

I have taken what you have given and I have soiled it, spat on it.

He did not say, I have protected your children, for he had taken those children by force. He did not bury his face into the forest floor, rage into the night, beg the parent to maim him, twist the life from him. Excuse, self-abasement, had no place in the presence of the dreadful wisdom of the parent.

By unspoken command his head was raised and, neck craned, he gazed at the bole above, its coat of cold pale fire-light glimmering. The parent stared down at him, at the being at its foot who had stabbed and rent it, ripping the two tiny doll-bodies from its flesh, and he thought it no more felt the absence of its spawn than the ocean resented a child’s scoop from its rim. The removal had extended its grasp, no more; had spread the reach of its power. And he knew then that the power remained that of the parent, could not be transferred, and that he had given nothing to the man.

This time, as he made his way back, the light remained, his footfalls true and effortless; and once, when he paused to slow his breath, he felt the glitter of tears on his face.

Noon, and the sun was his spotlight, its bright stare proper for the occasion, yesterday’s milk-filter gone. Kessler’s tunic shone blackly, the sleeves rolled up. His wife had shone the buttons well: a favourite dress, a smile of affection, would be her rewards, were owed to her.

The tableau was imbalanced: before him, the perfect chaotic spontaneity of the children, thirty again, in their half-circle, the force of their expressions combining a few feet ahead of them and channelled at him, no surprise in the solemn faces, no wonder at the unfamiliar scene. But to his left, wavering at the interface between illusion and invisibility, the brittle figure, hands clasped in front of its scrawny sack-clad belly, and he fancied its eyes were on the crates at his feet.

In the bright silence, he reached into the box at his right hand and clasped the jointed cross and lifted the girl-puppet into the light. He had mastered the technique of watching the puppet with one eye, his other on his audience, and he was looking for a ripple of surprise. He was disappointed to see none. Perhaps the old man himself had sometimes begun stories with the girl-puppet rather than her mate. His fingers felt more natural, more at ease, manipulating this one.

‘Here I am, all alone, with nobody to play with.’

He felt a flicker of satisfaction as he heard his voice, normally a carefully modulated tenor, now raised perfectly into a little girl’s plaintive murmur. His technique was expert, the wooden hands deftly manoeuvred so that they appeared to be clasped before her in dejection. He breathed, as the old man had taught him to breathe, drawing the vastness of the forest behind into his chest. His scorn and disbelief, which had at first threatened to deafen and blind him to the elder’s instruction, he had learned to suspend: strategy was all, for now, until he had made the power his, and then the pathetic superstitions would be tossed aside, broken and dead.

It was not until the boy-puppet, Tomas (as he was now called; the names would need to be changed) stood and jigged beside its companion that he became aware of how completely he had given himself to the ‘strategy’, for he realised that he had not been watching his audience with one eye, had not, in fact, been conscious of seeing anything at all. He spoke and his fingers and his wrists played, and he saw that the children’s gazes were on the puppets. He scanned the faces quickly, the shadow of an impression flitting almost beyond the reach of his awareness until he grasped and identified it. The children’s eyes were not moving to follow the bobbings and weavings of the wooden figures; seemed, in fact, to be focused beyond the puppets, beyond him.

He was gripped by an urge to look behind him at the forest and he resisted, staring instead at the dancing figures. Their motion drew his gaze, distorted the perspective so that the puppets appeared taller, their heads now at the level of his waist. Then he realised his hands had stopped moving.

From behind there was an awful pressure on his back, and he felt himself impelled forward towards the skipping marionettes. He could focus on them now without lowering his gaze from the horizontal, and as the round wooden skulls swivelled and the painted grins faced him, he saw the children, risen to their feet and grown huge, approach.

His hands flailed at the sky, his feet jerking and scrabbling in the dust until he was grasping nothing yet was somehow lifted from the dirt floor, his head bobbing so that his vision trembled. He opened his mouth to shout, found his lips clamped shut and curved downwards obscenely at the corners, a parody of tragedy between the dual gaieties of Frieda and Tomas. He tried to blink, could not: a not-face to accompany his not-limbs. He wanted to look above him and, when he felt a tug, let his head loll back.

From his hands, from his head, strings converged in a foreshortened steeple to a wooden cross around the centre of which curled the gnarled knuckles of an enormous hand. The cross and the hand obscured most of the old man’s face, one yellow eye visible peering down across the wildness of his beard. A twitch of the hand and he felt his head bounce forward again. Knees and skirts and ragged small shoes hovered before his gaze, and were replaced gradually by giant faces as the children crouched to look at him. He found it difficult to focus on any single point, his movements were becoming more rapid, more complex, but nevertheless he picked out one face: it was a little girl, her tiny mouth and huge eyes solemn, a staff of wood grasped in both hands across her lap.

He could not blink, he could not move his limbs, he could no longer even feel the movements at his joints, his awareness shrunk to the field of vision directly ahead of him and to a vague sense of self within the confines of his tiny head; a self so purely passive he marvelled at it. He had known passionately all his life that this state was achievable, had held on to this belief in the face of defiance and ridicule; how delightful, how ironic, that he, who had striven to cultivate it in others, had now attained it himself!

He found himself facing the girl-puppet, Frieda, and the way they whirled and dipped in tandem made him realise he was dancing with her. Her face, so crass and gaudy before, was beautiful, he saw now that he was close. They were spinning so fast that the wood was no longer behind but formed the walls of a tunnel around them, and he was dimly aware that others had drawn near, the adult villagers and even, he fancied for an instant, his wife, his son. The old man, the children, the forest, were his masters, immense and absolute, best ignored: for here was Frieda, and Tomas who had joined the dance and smiled and nodded at him, and here, among his new companions, he felt at last that he truly belonged.

Finis

Comments:

<< Home

Goodie. Back from my hols and see I have a nice juicy crop of Footerings (Footlings?) to dig into later. Just a flying visit for now. Back in a bit with a no doubt pithless comment to make. Children, haircuts, cat's anal glands to attend to first before I can settle into blogland.

I was completely absorbed, Footsie. I like it a lot. It was darkly magical and starkly

layered - the clinical then the organic, the polish and the peeling; you can tell you're a doctor.

I liked that Kessler looked into the old man's yellow eyes and didn't see one of the things he felt in himself; the idea that evil is something added not something missing. I don't know why that seems comforting - maybe because then the default state for a person must therefore be good. Dunno.

But then the yellow eyes seemed sinister themselves. I think on the old man's last visit to the tree he carved a Kessler puppet. That is sinister, given the ending and makes me wonder who the other two puppets were or had been. And what was the deal with the wife? I have to read it again, I think.

BTW, I liked the liturgical style for this. It added moment to each paragraph. But I, like our Charlie-boy apparantly, listen to a lot of Leonard Cohen so I guess I like stuff spread richly sometimes - you do it very deftly though and The Woodborn was never

too heavy - all in the wrist, innit? ;) And besides, that style helps in creating a creepy mood of abstracted enchantment - things turned a wee bit on their axis - that you nailed.

I know little of such things but I say keep trying to sell that story. It is dense, yet still moves in a direction - just like a short story should be, it seems to me - some point midway between poetry and prose. I loved it.

layered - the clinical then the organic, the polish and the peeling; you can tell you're a doctor.

I liked that Kessler looked into the old man's yellow eyes and didn't see one of the things he felt in himself; the idea that evil is something added not something missing. I don't know why that seems comforting - maybe because then the default state for a person must therefore be good. Dunno.

But then the yellow eyes seemed sinister themselves. I think on the old man's last visit to the tree he carved a Kessler puppet. That is sinister, given the ending and makes me wonder who the other two puppets were or had been. And what was the deal with the wife? I have to read it again, I think.

BTW, I liked the liturgical style for this. It added moment to each paragraph. But I, like our Charlie-boy apparantly, listen to a lot of Leonard Cohen so I guess I like stuff spread richly sometimes - you do it very deftly though and The Woodborn was never

too heavy - all in the wrist, innit? ;) And besides, that style helps in creating a creepy mood of abstracted enchantment - things turned a wee bit on their axis - that you nailed.

I know little of such things but I say keep trying to sell that story. It is dense, yet still moves in a direction - just like a short story should be, it seems to me - some point midway between poetry and prose. I loved it.

Good one, Pi!

Mr. Eater, is "It's so cold in Alaska" a general observation or is London not cold enough for you? Are you moving?

Mr. Eater, is "It's so cold in Alaska" a general observation or is London not cold enough for you? Are you moving?

I like it!

It ends well, and the story seems concise and coherant.

Did you say you were unable to get this fun yarn published? That's a crime, as it is one of the better short fantasies I've read...

It ends well, and the story seems concise and coherant.

Did you say you were unable to get this fun yarn published? That's a crime, as it is one of the better short fantasies I've read...

Sam, SheBah, Pat and SafeT: thanks, I really appreciate your kind comments. I might have a go at rewriting this story for publication one day as I still like the idea but cringe at the pompous, sturm-und-drang prose. It was originally about 50 per cent longer but I trimmed it down to meet the requirements of a couple of fantasy/SF/horror magazines I submitted it to. One of them, The Third Alternative, has a very nice editor who sends personalised, handwritten rejection letters (or at least he used to, about five or six years ago). He said he liked it but didn't think it was stylistically quite right for his magazine.

If anyone's still there, I can't post to this blog for the moment as there's something up with Blogger. Is it just me or are others experiencing this problem?

If anyone's still there, I can't post to this blog for the moment as there's something up with Blogger. Is it just me or are others experiencing this problem?

Oh, and Sam: no, I'm not moving and have not moved. The Alaska observation is a lyric from a Lou Reed song, Caroline Says (II), from his Berlin album.

Lou Reed eh?

Plagerist!

Still not read it yet.

Got to do it justice man.

SPCB, says it has Le Carre-ish parts to the mixture.

We'll see.

Plagerist!

Still not read it yet.

Got to do it justice man.

SPCB, says it has Le Carre-ish parts to the mixture.

We'll see.

You'll never read this story, Maroon, be honest. Not that I blame you.

For a while, I couldn't post pictures on Blogger. Now I can, but for some reason this post remains irritatingly resistant. Can anyone explain why? Is it perhaps because of the size of this post?

Post a Comment

For a while, I couldn't post pictures on Blogger. Now I can, but for some reason this post remains irritatingly resistant. Can anyone explain why? Is it perhaps because of the size of this post?

<< Home