Wednesday, May 31, 2006

The Woodborn (part two)

His wife, in the mirror, made a small gesture with her hand, her eyes on his throat. Kessler saw and fingered the knot of the tie. Long ago, she would have touched it herself. It had not been long before she had learned.

At the table, she was silent. He asked why.

‘A letter came this morning. From Michael.’

Long ago, she would have replied: nothing. She had learned.

‘Let me see it.’

Their son had obtained the results of his examinations. He had achieved distinctions in the sciences and mathematics. Kessler folded the letter. His wife watched his eyes.

‘It qualifies him. He will be accepted for engineering,’ she said.

‘Would. He would be accepted, were he to apply.’ He was irritated with himself. He had assumed discussion of the subject had ended months earlier. He had not the time, now, to correct his error. He stood, and was surprised when she rose with him. Her eyes met his, slipped, rested on his cheek.

‘He wants it more than anything else.’

Later, he would finish it. He would explain again that their son would enter the Academy, that he would excel and be marked early on as an officer, that he would continue his father’s work in the provinces. He would explain the importance of the military way, its place at all levels in the new order, and she would understand the reference to her behaviour this morning, and this time she would not forget. Now, he had other work to do.

He felt her eyes dropping from his back, and walked out to his car without looking at the guards on either side of the door of his house. His driver was waiting behind the wheel. The journey to the headquarters was twenty minutes of dust and machinery clatter, trucks lumbering aside in clumsy respect as the driver steered a smooth path through the streets. From the back seat Kessler watched three squat vehicles surrounded by shouting men haul a giant stone statue erect, and the men cheered with a single voice as they stared up at it. He turned to look at the statue through the rear window as the car passed; it was of a man in general’s uniform, one hand on the sword at his belt, the other outstretched, palm down, shielding the people gathered at the feet. As the scene dwindled, others were coming out of the houses, women and children and the old, to stand at the base of the statue and leap and laugh beneath its reach.

He spent half an hour at the headquarters and then he was in the car once more, a personnel carrier behind and two smaller vehicles ahead. His lieutenant, Veneman, sat in front beside the driver, his head turning to the side in a single cog-wheel movement each time Kessler spoke. Soon the city was behind them, crowned with a fog of dust that scattered the pale eastern sun. Ahead, the road dropped steeply into tree-shadow and the sharp sap of pine cut through the diesel stink.

The village was five kilometres down a dirt track that had been worn down by feet and wheels. The track widened into the village centre, a square bordered by ancient stone-walled houses, a church to the right, what appeared to be a school building on the left. In the middle of the square was a fountain, a statuette of a woman holding a pitcher on her shoulder from which water trickled into the fountain’s basin. Beyond the buildings was the forest, as though the village had gently nudged the trees aside to ease a space for itself. Nine or ten people stood around the square, women with pails and bundles, old men talking over pipes. Far away, a bell rang, two notes repeated over and over and slightly irregularly as though it were being rung by hand, the sound dissipating into the trees.

Kessler motioned to the driver and the man flashed his lights and the two cars in front stopped. He sat in the back and waited for the driver to open his door, watching the people who stood around the fountain. They looked at the vehicles, their eyes incurious, and the men sucked at the stems of their pipes and the women hefted their pails but did not lower them. Lessons there were, and to be taught quickly. Outside, he gave his orders briefly, and there was fast motion. He watched as the gate of the school building on the left bulged and then flung out a spume of children, not raucous but solemn, drab in colour as they filed across the central cobbled area and down the road away from him. Few of them glanced at him, at the cars.

Kessler checked the sharpness of his collar with his fingers and the cold holstered metal at his belt and set off after the children, and when the lieutenant Veneman stepped to his side he murmured ‘No’ and the man fell back. He kept up, though the line before him moved quickly, and when after half a mile it slowed he steadied his pace so that he hung still further in the rear. The village had almost ended by now, the trees sucking in the road so that it was little more than a sand path. The stone fronts of lone houses peered between the trunks.

The children, perhaps thirty in number, ordered themselves spontaneously, the tallest standing at the back, the smaller ones squatting in the dust in a ragged semicircle before a tight twist of thick boles. At the base of the trees were two wooden crates, three feet high and as broad, their sides carved with leaping figures. The children had been voiceless throughout the journey and were silent now; they did not fidget, they did not laugh or squabble.

A man stepped out from between the trees. He was old, his spine stooped, his hair and beard sparse and drifting as a web. Kessler could see nothing of his eyes, but the raddled cords of the brown arms that protruded from the filth-rags revealed a strength which spread down to the spindled clicking fingers. The man stopped at the boxes and raised the top off one, laying it down carefully and then with equal gentleness grasping into the depths and lifting out a twitching elongated bundle of wood and string and paint. The man held the puppet high and as he reached with his other hand into the box the tangle from his first hand began to take on form, thickening and jerking so that four appendages grew and tested themselves and all at once there were two grinning impish beings, their clothes and their noses and ears ridiculous and compelling, and a sigh of recognition riffled through the watching group.

The old man was speaking, his voice high and keening, rising to an absurd falsetto to represent the speech of the female marionette, slipping to a tenor for the male. Kessler was aware of the vague shape of a story but he paid little attention to it, less still to the movement of the characters in response to the rippling of the ancient fingers. His eyes slipped across the unmoving audience, now settling on a wide-mouthed profile, now resting on the back of a shorn head which by its stillness communicated fascination, rapture. With the frozen tableau before him and the flickering of movement and sound at the periphery, he felt the slow swell within him until he could no longer contain himself and stepped forward so that the tips of his boots were inches from the cusp of the half-circle, a bare brown back exposed where the child’s shirt had rucked up out of the tattered trousers. He was no longer hidden, no longer in the background, and the puppets continued their dance, and their master’s eyes were closed as his hands glided and his lips spilled their legend. He stood, erect, in the sharp sheen of his leather and keen-pressed cloth, and the children’s heads did not move at the shuffle of his boots in the dust.

The elder stood, his stoop gone, the puppets upright but motionless, his eyes closed, and the black and brown and gold heads before him were still also, and through the silence the whisper of the wind started in the engulfing forest and then died, as though cowed.

The eyes opened and he gazed into them, and there he saw what he had not seen in the eyes of the man he had shot in the last village, in those of the pathetic hundreds who had raged and smirked and eventually shrieked and bled at his feet. He saw, in the yellow stare, what he himself felt, what the ancient possessed, and there was something else he felt, which he did not see, and the rage rose in him and he said gently: ‘Good morning. I am Colonel Kessler.’

‘Who are you.’

The tone soft, the words pared off like slivers from a block. He gazed at the bright yellow and red and green of the ribbons at the left breast. He thought he should look at the eyes, but he was old.

‘Who are you.’

He did not lift his eyes. ‘I have told you my name.’

‘Yes. I am not asking for your name. I am asking who you are.’

I am an old man. I am a villager. I am a puppeteer. ‘I don’t understand.’

There were three in the room, three that creaked and shone when they moved, but the man with the ribbons was before him and was the master. The man with the ribbons, the colours, stood at the other side of the desk at which he was sitting.

‘The children came to you, immediately.’

He said nothing.

‘Do they come to you every day?’

This, he could answer. ‘Yes. Those who -’

Silence, and he knew he would have to end it.

‘Those who are permitted. By their parents.’ Then he looked up at the face, but its sharpness was painful and he spoke quickly so that he could drop his gaze again. ‘I don’t know who they are. I don’t know their names, or who their parents are. I don’t know which children are forbidden to come.’

‘How often do they come.’

‘Twice a day. Noon and dusk.’

It continued: is it always the same story, do you have other puppets, do you talk to the children directly. His third no and he peered up quickly again, afraid that his replies would be interpreted as insolent, but the eyes on him were steady. He dared to hold the gaze, saw the mouth stretched thin and taut across small neat teeth, fancied he could taste the sour tang of the man’s breath in his nostrils. He stared at the eyes and waited for the hate, the contempt. He saw fascination, eagerness, even.

Emboldened, he murmured, ‘Please don’t punish them. The parents, either… They don’t know…’

The arms were braced on the table, the face closer, and he felt the eyes. Beyond, unfocused, the other two creaked, coughed. He tried to concentrate on them, the non-essential, the banal, but the eyes burned and probed and he suddenly slumped forward on the desk and gave himself up to the engulfing presence above and before him and the thin lips opened with a tiny dry husk and all he could see were the ribbons, green and gold as the forest as the voice hissed: ‘The Renewal requires it. You will show me the secret of the puppets.’

For a minute, he was gone, bobbing away on a gentle current from the tableau of interrogators, and he was laughing, at the child-awe of the tone, the hush of the phrase: The Secret of the Puppets. The earnest upturned face, pink and scrubbed free of smudges, above the fierce innocent important ribbons, beckoned to his compassion, his passion, his desire to fill with his wisdom, and he smiled because it would be easy to speak, easy and therefore worthless; with his hands he lifted Tomas and Frieda from their boxes and with his fingers he gave them life, and as they soared and danced he pulled to the side, away from the forest, he was too close to the forest because the branches were grabbing at him and wrenching and he could not go with them, had not finished.

His fingers flicked a signal and the sergeant let go of the man’s ear and the twisted body jolted back into the chair, the lids blinking slowly. Kessler leaned his forearms on the table and brought his face close so that the eyes swam at him through their egg-film.

‘You will stay focused.’

The tip of the tongue probed greyly at the withered lips. Kessler reached out and gently tilted the head back with his fingertips; it was less easy for the eyes to avoid his.

‘You say, there is no secret.’

The eyes hovered beyond his, in their tortoise hoods. The face was a gnarled trunk of ash that sprouted matted grey moss. The mouth-cleft split and writhed soundlessly.

‘But the children came to you, today. They came to you and I was there, with all this.’ He flipped a hand at the man beside him. ‘All this, and they watched you.’

Movement, then, a lifting of the eyes, rather than the head, and Kessler grasped for the meaning, pride, was it, no, that was too obvious, and then he saw it and was enraged and grabbed the ancient tree-man, seized his foul splintery scrag-hair and jerked him up out of the chair, and beyond the flicker of pain the expression remained. He twisted the man from behind the table and toward the door, his sergeant already wrenching the lid off the first box, the second, and flinging the limp clacking tangles of wood and string through the open doorway to sprawl in the dust and stone.

His face was close to the elder’s now and he noted the first twitch of doubt. The triumph soared within him as he nodded to the sergeant, unsmiling. The arc of gasoline glittered and the wood and string lay stinking and anointed in the sun.

‘I will.’

He nodded again, and in the sergeant’s hand the rasp of the match spat a tiny cone of fire.

He felt the elder sink and lowered his arm, controlling the movement so that the creaking tree-man, the nothing, knelt with arms loose, held upright by his hair, and through the lank matted swathe a sob, a murmur.

‘I will show you the secret.’

Comments:

<< Home

"Hi, i was looking over your blog and didn't quite find what I was looking for."

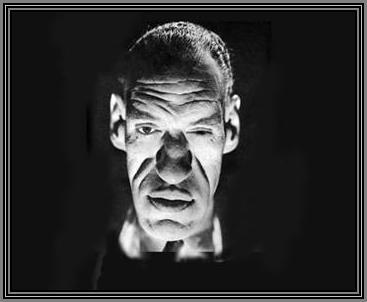

You better fucking believe it. Haven't read it yet. I'll get back to ya. The puppet pictue..........

You better fucking believe it. Haven't read it yet. I'll get back to ya. The puppet pictue..........

That anonymous comment is staying because it's hilariously apt - I have tried to make money with this story before.

Doc Maroon: yes, come to think of it that boy puppet does look familiar.

SB and SafeT: thanks. The final part will go up at the weekend.

Doc Maroon: yes, come to think of it that boy puppet does look familiar.

SB and SafeT: thanks. The final part will go up at the weekend.

Hi, i was looking over your blog and didn't

quite find what I was looking for. I'm looking for

different ways to earn money... I did find this though...

a place where you can make some nice extra cash secret shopping. Just go to the site below

and put in your zip to see what's available in your area.

I made over $900 last month having fun!

Oh, do fuck off, you pustulating sore.

quite find what I was looking for. I'm looking for

different ways to earn money... I did find this though...

a place where you can make some nice extra cash secret shopping. Just go to the site below

and put in your zip to see what's available in your area.

I made over $900 last month having fun!

Oh, do fuck off, you pustulating sore.

______________

This information is very useful. thank you for sharing. and I will also share information about health through the website

Obat Sakit Mata Belekan Alami

Cara Mengatasi Diare

Obat Sariawan Alami

Obat Penghancur Batu ginjal

Obat Sakit perut melilit paling Ampuh

Post a Comment

This information is very useful. thank you for sharing. and I will also share information about health through the website

Obat Sakit Mata Belekan Alami

Cara Mengatasi Diare

Obat Sariawan Alami

Obat Penghancur Batu ginjal

Obat Sakit perut melilit paling Ampuh

<< Home